In the 1980s and 90s, Sheila travelled to Pakistan, specifically to Baluchistan, as Cultural Advisor to an Italian research project, led by an Italian Professor Valeria Piacentini Fiorani. While she was alternately exasperated and enthusiastic about these journeys to this remote area, which required endless red-tape and permits, she was thrilled that her lifelong interest in Indian Ocean culture led to her work on lacquer crafts and craftsmen being published in Baluchistan- Terra Incognita (2003).

I shall summarise and quote from her diaries and photographs from the respective years of the expeditions.

1986

The first journey lasted about a month and involved her ping-ponging between Karachi, Hyderabad, Karachi, Lahore, Karachi and, finally Quetta, before returning to Karachi.

In Karachi they were staying at the nurses’ hostel at the Holy Trinity Hospital, all courtesy of the Catholic Bishop Lobo, ‘a very well-organised serious man…his eye misses nothing…surprisingly he isn’t able to accept that as a Christian community in a Muslim country, the church isn’t always popular’. The Catholic tentacles, via the Italian origin of the project, were to prove extremely useful for accommodation and transport arrangements.

The ‘good Bishop’s car and driver’ whisked them off to Hyderabad where they stayed in the Bishop’s House, in order to visit craft centres and the museum as part of their cultural orientation. The Hyderabad Bishop was ‘very jolly and happy-go-lucky’ and enjoyed his home-made wine – ‘plum and beetroot …even to my homemade palate seemed a little strange’. Unfortunately there was no cook and Sheila took ill. She was vegetarian and suffered greatly on this trip – she had eaten nothing but white bread during her stay – so the journey back to Karachi via Thatta was difficult – ‘I couldn’t enthuse about anything today and didn’t take any photographs which is a pity’ – where there is a mosque built by Shah Jahan; Bhambore, where there was a museum; and Kaburishan, a cemetery with some unusual graves.

Karachi

Back in Karachi, Sheila was on a quest to find out anything about Arab Chests, so she followed up lots of contacts – academics, friends of friends, the British Council. In the old copper and brass market her guide ‘tried hard to find something to interest me, but either he didn’t understand what I wanted to see, or there was nothing like it around, or he thought he could divert my thoughts in other directions…it was all to no avail. I felt frustrated.. this was my last chance…I was by now quite on my own and had no idea when I was likely to hear from Valeria again.’ This was a constant theme of her relationship with Valeria who was what we now call ‘flaky’ and what mum called ‘temperamental’!

Nevertheless she was determined to make the best of it – something she had done all her life, so her diaries are full of descriptions of her observations, and really bring to life the places she visited and the adventures she had. A brave woman!

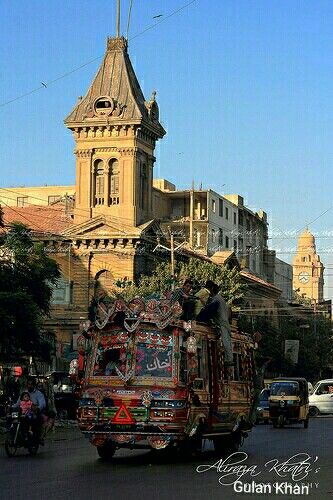

Karachi is a sprawling pretty new place – wide dual carriageways, many trees and shrubs and plants everywhere – rather reminds me of parts of Cairo. The trade is arranged in areas so that you have. for example, all electrical household items together then you move onto motor spares, cloth, curios and so on – very oriental. …Not really so much rush and pressure as in India but nevertheless quite crowded. Both men and women wear baggy trousers ending in a stiff cuff, and a loose long shirt with split side seems over.

Quite heavy traffic, cars mostly Japanese, horse-drawn carriages, quite smart with the horses appearing mostly in good order. Some motor rickshaws and taxis. Buses are magnificently plated with stainless steel cut-outs all over, painted in bright designs and all manner of chains and motifs dangling from the front and back bumpers. Some beggars, the odd leper, but not many. Very many men have beards, long hair all caps and all on the whole handsome. Women seem good-looking too.

…I don’t know why we don’t all die of carbon monoxide poisoning or become deaf, or even get knocked over in the traffic – the exhaust fumes, the incessant hooting and the disorganisation of the traffic make walking in the street somewhat unpleasant. The people are really very kind and helpful.

She visited the Fishing Wharf, a long rickshaw journey: ‘you know when you’re there by the smell of drying, dried, rotten fish all mixed up together’. This was brave: ‘people were friendly and smiling – not a lot of English spoken. Polite too. I finished up with a cup of tea in the Fishermen’s canteen – not good.’

Lahore

On Good Friday she took the Awami Express. ”Pakistani 1st Class is more like Indian 2nd, only there isn’t the provision to lie down on 3-tiers…so I was faced with the prospect of sitting upright for the whole journey of 21+ hours [she was 66, just about my age as I write this and I would not have been happy]. Her neighbours were an elderly bearded father with two sons, a ‘tidy and intelligent-looking young man reading textbooks, and Mr Latif, an ex-naval officer, who helped her order lunch from the dining car and amused her with endless chat of life on the high seas – he was tickled that she too had been in the Navy – and helped her twist a piece of cloth round her head to keep out the dust – ‘looking like nothing on earth, I noticed when I went to the latrine’. Every two hours he unrolled his prayer mat to pray – he had specially travelled on the train so he could do so; one or two people asked him to lend it to them which he did. ‘ He was extremely generous is supplying me with a stream of refreshments: cups of tea, fruit – guavas sliced and sprinkled with chilli and salt, bananas, tangerines; a sweet in a piece of newspaper made of milk. But he didn’t take very much from me, we shared a soft drink and had to be persuaded hard to take fruit.

It was incredibly dusty and got quite cold around 4 am. The population kept changing and at some stage there were people lying on thin blankets in the corridor making passage very difficult. 2nd class next door seemed entirely blocked

The student helped find a cab and made a phone call to find out where she was staying.

The whole suburbs are extremely spaciously laid out, dual carriageway in parts with flowerbeds containing all kinds of colonial, colourful plant plants, annuals – phlox drummondii mainly, but beds of nasturtiums, petunias, cornflowers, gazanias, French marigolds, hollyhocks, beautiful antirrhinums to name a few, and also beds of healthy looking rose bushes just coming into flower, small blooms but colourful and arranged in various shades en bloc. We passed a wide canal which helps with the irrigation and seems to keep all this going.

Whilst in Lahore they saw the main places of interest:the Fort and the Badrishahi mosque, ‘neither in frightfully good repair’. They visited the museum ‘a very good one’ on Easter Sunday, ‘Im afraid none of us went to Church’.

In the afternoon they went to the Shalimar gardens, where there was a festival going on, ‘it took the form of crowds and crowds of people mostly from up-country, in their best clothes, children being treated to funny hats, balloons and plastic toys…there was an amusement park with giant wheels, roundabouts and goodness knows what else’. She found the gardens themselves ‘rather untidy’, although she admired the lake with its many fountains and pavilions.’It must have looked fantastic when it was all working.’

The following day, before she was to return to Karachi again, they set out for the old city bazaar.

Ugo [one of her fellow travellers] wanted copper. This was quite hard to find but we kept at it, getting deeper and deeper into the backstreets which became narrower and narrower. We saw gold silver thread from saris being reclaimed to burn and release the metal for use by the jewellery workers; all sorts of materials, kitchen utensils, electrical equipment, toys, tinselly things which look as if they were used for weddings, the whole place seething with people. In traffic you could hardly move and, if this is a poor country, it’s hard to imagine how it manufactures or imports all this stuff and who has the money to buy it.

We couldn’t find anyone to tell us where the copper bazaar was as no one spoke English but we knew we must be getting near as the shops/stalls began to stock pots and pans and, sure enough, on the corner there was one which had towers of large brass copper containers, one standing on the other to make a pillar of pots And we saw down a covered bazaar other similar pots, together with all kinds of other utensils. We had arrived!

Among the crowds we came across a man holding a particularly garlanded white horse, milk white with red toes and blue eyes. It must’ve been an albino, got up for a wedding, the groom rides on one. We took several pictures of this most unexpected sight, so bright and clean and shining with tinsel in the midst of all the clamour.

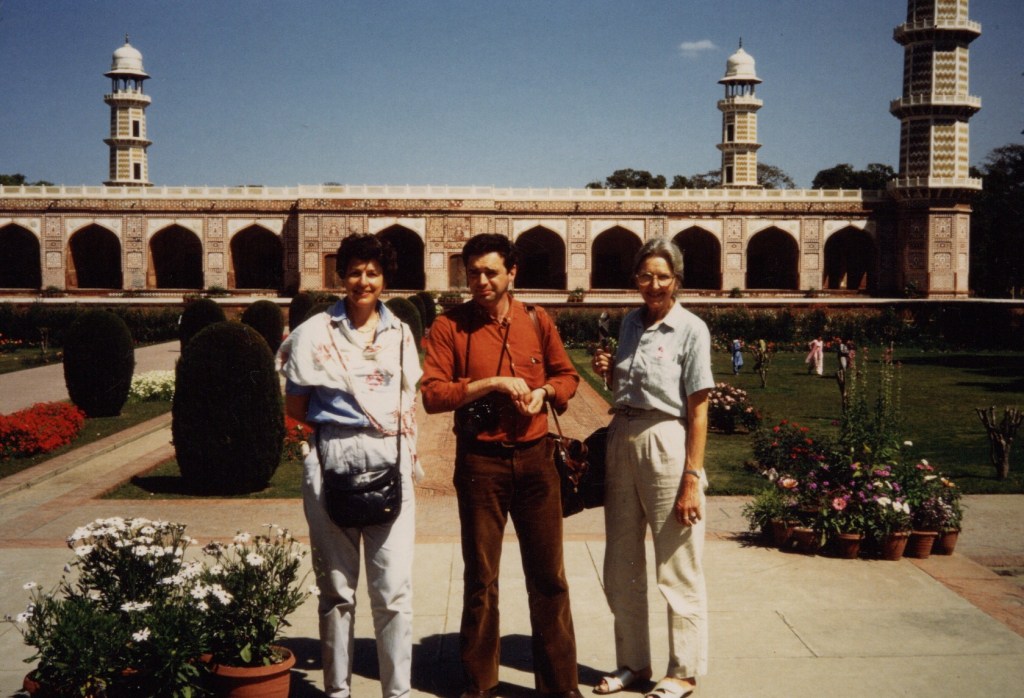

Then to Jehangir’s Tomb:

Somehow we crammed into a rickshaw. We followed the walls past the Badrishah mosque and Fort and over the river and railway line into a rather seedy rundown district However, through the gateway of the walled enclosure containing the tomb, you could see it was much tidier and well looked after. Inside we stopped for a cup of tea .

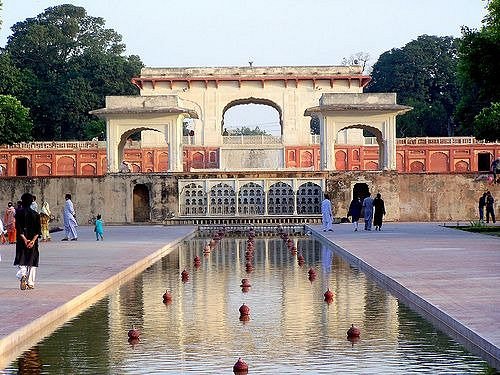

The walled area around the tomb was divided into two large courts with lawns and gardens beautifully kept, lovely flowers and tall trees. We traversed the grass towards a gateway with surrounding buildings which you pass through, up steps and then down again into the court where Jehangir’s tomb lay. This side of the complex was even more beautifully kept.

I stood at the top of the steps and admired the gardens: the path leading to the tomb was flanked with flower gardens and clipped Cypress trees and there were many pots of gazanias and cinerarias.

As we approached the tomb irrigation water was being released onto the grass under high trees and children women were paddling and dancing about it. We stopped at a central marble fountain halfway down the path to the tomb raised on a square plinth. It had clean water in it. We surveyed the tomb enclosure built of pink sandstone with at each corner of fine high minarets, Mogul-domed, the pillars facing in a horizontal zigzag stones – most unusual.

She returned briefly to Karachi ‘to fulfil commissions for Valeria’ before setting off on a coach to Hyderabad for a couple of days, and proceeded to make her research calls, but as per usual found herself being batted from person to person, drinking copious amounts of tea. ‘As ever, they always say, yes, chests are here and before long you’re engaged in a discourse involving Mohenjodaro and Alexander in 355 BC. They never really get the hang of what you’re really interested in is comparatively recent. However, I struggle on, a cup of tea is produced and is very welcome.’

Quetta at last!

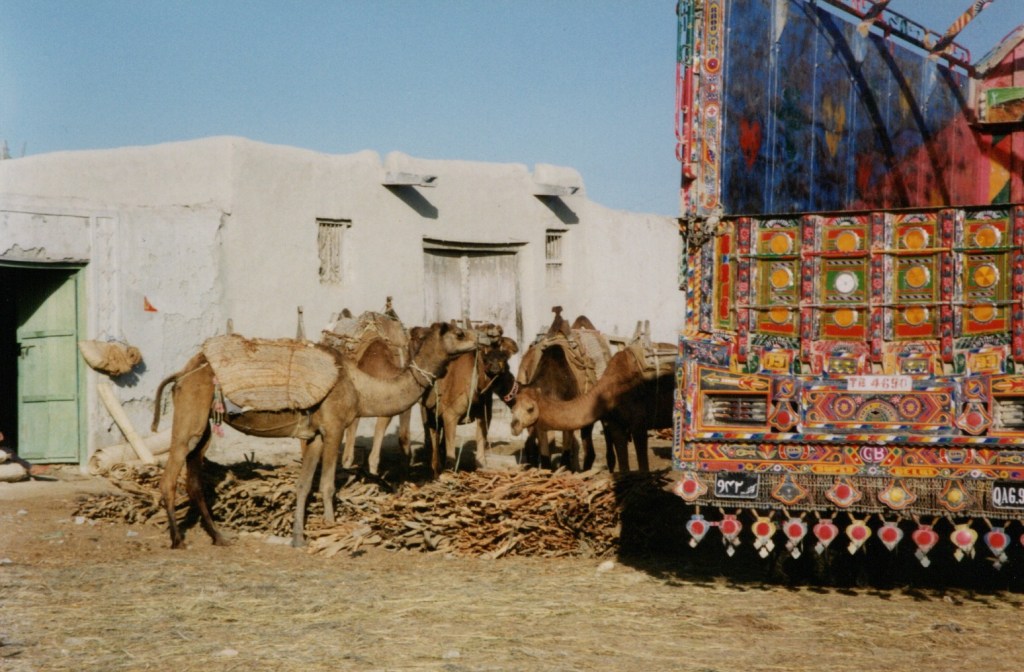

Today is the day I’ve arranged to go to Quetta. The road passed first through scrubby thorn then stony desert then sand stones and eventually with giant grey beige rocky mountains on the horizon, we finally drove through a pass into more plains.

This would probably have been Bela up towards Kalat, small fields of sparse whiskery wheat appeared the more northerly we went the more flourishing they were – if flourishing is the word. There were a few villages and even the places not on the map were nothing much beyond a petrol station and a few huts.

Water seems to be bored for there were tanks and channels leading to a field but these flow few and far between. It really is an unhospitable area – dry stony and rocky. Here and there you see the tents of nomads, black and brown, and flocks of delightfully woolly sheep, white sometimes with black, mainly dark-headed, goats; camels too, grazing or tethered or being ridden or driven. Occasionally you pass groups on the move, the round tent frames bound on the back of the donkeys, the ends sticking up.

Another rather slick round young man joined us; he was rather effusive, said he was in banking had been here there and everywhere, been in England et cetera. We exchange addresses, I rather dubiously. His friendliness seemed to exceed even the usual hospitality. Back in the bus he kept passing me sweets and even came and sat next to me for a bit as he thought I looked bored.

The countryside if it can be called that was by now more cultivated quite a lot of fields of wheat and some lined with trees coming into leaf. It’s spring. Children by the side of the road offered bunches of brilliant coloured flowers. I thought they might be nasturtiums but they turned out to be wild tulips.

I was anxious to get to the Bholan pass which was said to be more spectacular than the Khyber Pass before sunset. At last I thought we were there, but we came to a customs post where my new friend jumped out, embraced everyone and held up the bus for a full five minutes The elderly (how can I say this? but he had a grey beard and certainly wasn’t young) driver waited for him patiently and when he got back in he shouted to me that he’d been in the customs once and knew everyone. As he told me he was also a journalist, actor TV producer and writer I began to wonder just who he was. He showed me his press card.

The sun was setting and it must’ve been 6.45 by the time we drove into Quetta. The bus stopped by the side of the road and strange to say Valeria and Ugo and the Suzuki from the Saint Joseph’s convent where we are staying – were just passing at that moment, so it was a quick turnover for bus to the mini bus.

They are staying at Saint Joseph’s Convent which is ‘delightful, carpeted and has bathrooms, even a bath with hot water, fridge and every possible comfort.’

Quetta itself is a modern city having been devastated by an earthquake in 1935. It is laid out in a broadly geometric plan and few of the houses are more than one story. It lives in a plain surrounded on all sides by grey craggy mountains; even today there are traces of snow in the crevices for it has been a cold winter and fruit and flowers are all late this year. In the morning there is sometimes a mist and you can’t see the mountains, but this clears by the evenings when they take on a pinkish glow .

The streets are lined with the usual mixture of shops: the first time I’ve seen a display of ammunition – gun cartridges in varying sizes arranged on a circular plaque among soap powder and face tissues.

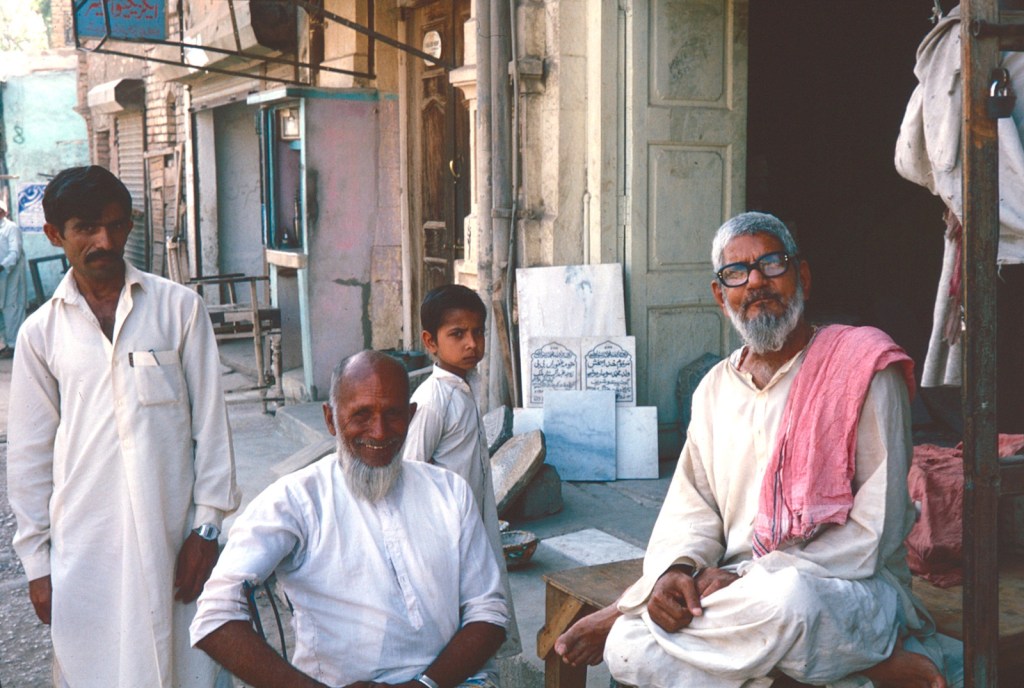

As for the people they are an array of all kinds of tribes and races. Hardly anyone wears western dress and the varieties of headgear are fascinating. There is the Sindhi hat, a pillbox with a cut-out front…in various materials from gold and silver thread embroidery to a sequin and mirror inlaid ones, on backgrounds of different colours. Many men wear turbans, some of which are massive, must contain yards and yards of cloth which they wind around so casually and effectively that you can’t think how they do it without the whole thing collapsing.

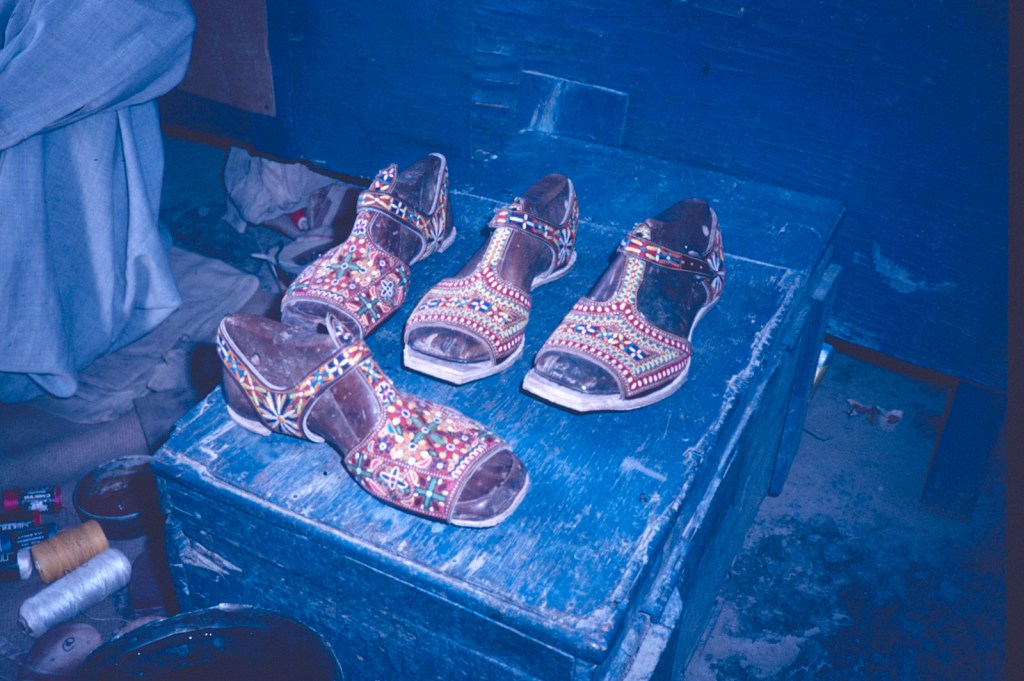

The shalwar khamiz, baggy, very baggy, trousers with a matching loose shirt flopping down to knee length or below is invariably from worn by men, in white or some sober colour and over everyone’s shoulder a shawl is draped. Perhaps this is for the cool season. A great variety of footwear is worn; some men wear traditional slippers, embroidered with gold, silver or coloured threads with high pointed-back curly toes, whilst others preferred chappals which could also be embroidered. It is strange to see highish heels albeit blocky and sturdy on some shoes, and you can even see men wearing ladies sandal types. Beards and moustaches are de rigeuer.

As for women, you hardly see them in the streets. They all wear feminine versions of the shalwar khamiz, and scarves all over their heads and faces but you also see some wearing the all-enveloping burka, a kind of cap fitted to the head from which flows a tent-like cloak down to the ground with some sort of lattice, through which they see.

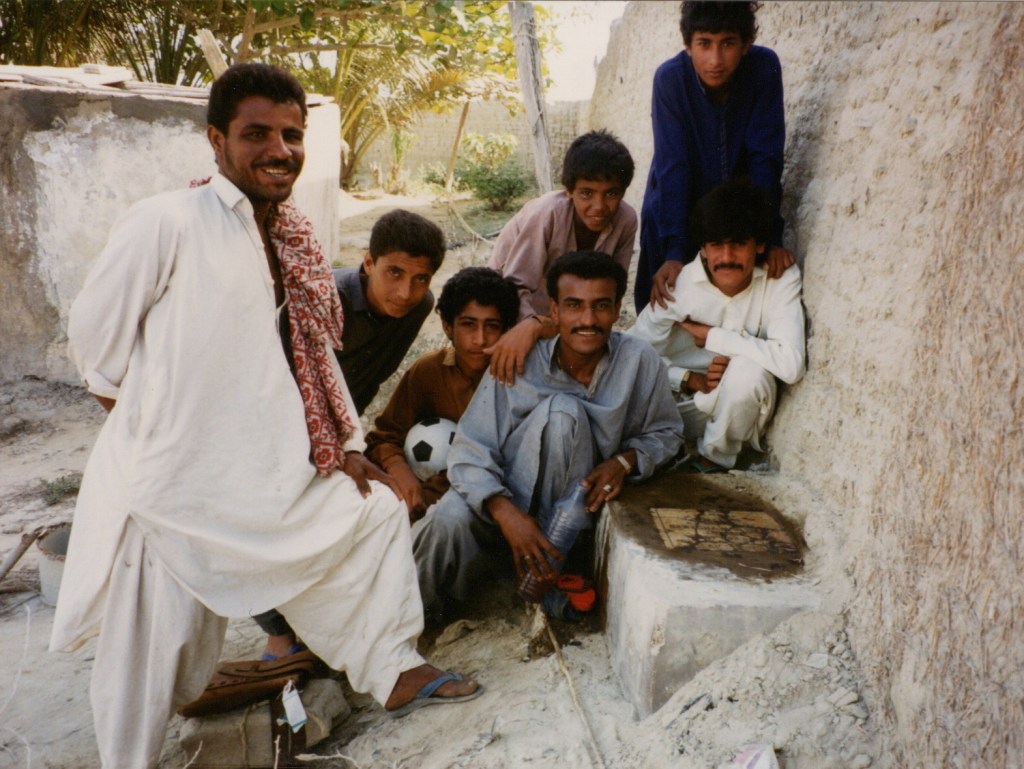

Lots of little boy urchins: they are employed from a very young age and you see very small ones around five or six years doing jobs in the tiny silversmith booths, cleaning elements for necklaces bangles and so on by the use of age of traditional methods.

They were waiting in Quetta for a permit to get to their real destination – Makran. ‘It really is a toss-up. They are very suspicious of foreigners, and in fact here in Baluchistan the Russian/Afghan forces are more favoured than the Afghan Mujaheddin and the numerous Afghan refugees who are living in the country – lots of camps round this area – are much resented.’

They spent a week hanging about. A message came through from the Embassy in Islamabad that the director of antiquities does not favour the project. ‘This sent Valeria into hysterics – she gets very excited, her voice gets louder and louder.’

While waiting around they did a bit of shopping. ‘I bought two kelim pieces for Vicky, saddlebags and a flat square which is meant to be a table cover.’ See below!

In the end Ugo and Valeria left Sheila again. Undeterred she went on a couple of trips with newly-found lady friends to Lake Hanna and the Urak Valley.

The lake was a milky green-blue surrounded by barren hills. the ladies enthused at its beauty, then off down the Urak Valley, which has permanent water flowing through and though rocky hills flanked it, there were fields and fields of apple and other fruit trees, their blossom just fading. Every now and again flat roof mud houses by the side of the road or on the hillside, and people were working in the orchard putting on manure which they got from big heaps by the side of the road. The occasional bright pink blossoms of almond.

The greatest excitement of her stay in Quetta was a visit from the President Zia al Haq, ‘the city bristling with policemen…his cavalcade preceded by outriders, police jeeps, a car or two, himself in a limousine. All I saw of him was a languid hand in waving position and then more cars, police and finally an ambulance.’

So back to Karachi and home, mission not yet completed! Until the next time…