Sheila returned the following year with the Italian team; this time they hoped to spend more time in Baluchistan. However, on arrival in Karachi they were told there had been a lot of rioting in Makran and Turbat and people killed. ‘There is an underlying discontent about an American presence in the area, they had been there for five years and nothing to show for it – they are building ports at Gwardar and Pasni, said to be for Pakistanis, but feared to be for their own fleet…the troubles in Jiwani arose from complaints about lack of water and electricity…and the radio today reports of the shooting of some drug smugglers in Turbat so we seem to have arrived in the midst of turbulence.’

Finally, three days later they flew to Turbat. When they arrived, they could see columns of black smoke twisting upwards where lorries had been burned. They took their first walk through the town, ‘nothing open, not many people about, remains of blackened burnings on the road, broken glass and remnants of tyres…we were joined by an army friend and escorted back in the company of levies with bandoliers, men with lathis and three trucks of armed men. it wasn’t considered wise for us to be about as yet’.

They were confined to the rest house for the next five days, although they are allowed out to shop, escorted, but food was in short supply due to the riots. Their fellow guests were a group of Chinese ‘who are installing equipment of some sort. One speaks English and he’s lent us his tape recorder complete with Beethoven [and The Blue Danube], but as it works on electricity we haven’t yet been able to use it’. Each group buys chickens which they pool and feed together, ‘suitably marked’. Three weeks later Sheila remarks, ‘I am so fed up this ghastly food that I feel like going on hunger strike. I hate tenderly looking after the poor chickens, giving them rice and water, to see them hauled off and onto our table within the hour.’ As a vegetarian this trip was very hard for her. Most of the villages they visited feasted them on roasted or curried goat…

She was very frustrated by the bright lights and noise of the nearby American generator while they were all in darkness for most of their stay. This tape recorder turns out to be a useful diversion for their confinement, and when the Italian team began falling out, which they did for the whole trip, much to mum’s annoyance. She tried to keep her head down, doing the shopping and organising the catering, boiling up endless kettles of water which no sooner done than the others used it all. I can see her feeling martyred and victimised just from the way she writes. Really she should have defended herself more against their bullying!

When they were finally released for field work, they divided into two groups – one the archaeologists, comprising Valeria, her son Alessandro; Roland, a French archaeologist; and Guisepepe, an Italian topographer. In the second group studying culture were Sheila and an Italian anthropologist Ugo. However, they were always treated with suspicion – ‘ we keep getting visits from people who appear to be secret service, asking all sorts of questions. one unattractive large-nosed man with sunglasses seemed quite anxious about our morals but luckily it was evident that Valeria and I share a room and I, an old woman, cast an air of respectability.’ Wherever they went they were accompanied by levies – armed guards.

On the first day they all visited Miri Kalat, a castle overlooking a large oasis. but thereafter they split according to interests – when they could as there were interminable wrangles about cars, drivers and transport in general. Sheila and Ugo were free to visit villages, where they spent time with the women, exploring their homes, traditional dress and way of life; or in the fields looking at irrigation systems, called kerez, and learning about local agriculture and livestock. In the villages she was always on the lookout for Arab chests, which she was convinced would be there somewhere.

Hosht Kalat village: prize Zebu ox

There are long descriptions of the interiors of these houses, the finest of which were in a village called Hosht Kalat. They were hosted by Imdad Ali, whom they had met in Turbat and who showed them round his farm in the oasis.

At Imdad Ali’s farm in Hosht Kalat. The kerez at work, pollinating a date palm

Next we visited a more substantial house made of mud brick, plastered. It looked new and was extremely tidy. The owner Hussein was a man of around 40, trim and neat who’d been in the Omani army. His wife is called Zebu and she was wearing the most beautifully embroidered red dress – panels down the front, the skirt pieces topped by a triangle which conceals a pocket, the sleeves have bands of embroidery too. The dress was said to cost Rs.1000 and certainly it was worth it.

As for the house, it was breathtaking. Row upon row of brightly coloured enamel plates were hung on the wall, beneath which were shiny stainless steel plates also hanging in rows. There was a little glass fronted cupboard with special cups. Beneath this were four suitcases raised on wood blocks or upturned bowls to keep them off the floor. There was an iron bed loaded with a mattress, pillows and quilts; there were also pegs on the wall for clothes and beside the short wall opposite was yet another covered cradle swinging from a pole supported by legs at each end…

Enamel plates and china cups on display

In yet another village, after a lunch of roast goat, ‘very good, had to eat with the fingers… haven’t eaten so much meat for ages and Gulam produced a bottle of whisky which I gather cost Rs.300 (smuggled) and pressed us all to a drink, Valeria and I visited the ladies. There were lots of them, sitting talking and sitting on a wide covered veranda, of all ages from an apparent 80 year-old servant, the grandmother, wife, daughter, other servants and hangers on. They wore bright embroidered Baluchi dresses and the contents of a wardrobe was shown to us. The dresses seem to be made mainly of nylon and rayon or polyester, plain or printed, heavily embroidered on the front with panels and sleeves as before described. Jewellery was then brought out – this was all of gold with small gems mostly rubies…

Chests

Finally in a village called Kalatuk, where there was a fort which could be seen from the road, Sheila‘s quest was fulfilled.

I was told there were chests in the village and lo and behold in the house of Munir Shah, I saw my first shisham chests: four quite nice smallish ones which had been handed down on the mother side from the mother‘s mother, about 80 years ago. There were two others, not so good, outside the house

The women wear beautiful jewellery every day – earrings, two or three big ones to an ear, all gold with pearls, turquoise and gold beads, in the lobe. These are attached by cords which join up and cross over the head to the other side. Or they may be made of gold in a decorative chain with small stones from which a filigree gold pendant, also with stones may hang. On the arms are bangles, one particular one a continuous sneaky silver band twisting about 15 times is decorated on each extremity with relief.

I visited the house next door inhabited by the head of the family, an elderly uncle. Inside the house were five shisham chests – He says they all they called them that – which he had brought in Karachi 40 years ago. They were in reasonable condition. He told me that before Partition chests were made by Hindus – you could buy as you found or have made to order, but of course not now and that’s why you can’t find them today, though most houses seem to function happily with steel trunks or suitcases. The chests were bought by sailing boat or later, when the roads were opened, by road. They were bought for the use of the women of the family. They cost is between Rs.150-Rs.200 for small size and you could have secret drawers or not as you wished.

While in Turbat they were invited to attend a wedding and much whisky was drunk in the company of the Taxildar; on their return at about midnight they successfully interrupted a kidnap attempt – in Pakistan this is a customary what of getting a bride with no bride price. At the wedding there was a professional dancer/singer – perhaps this is her? Actually, probably not as the singer was of African descent…but I want sure how to get this photo included!

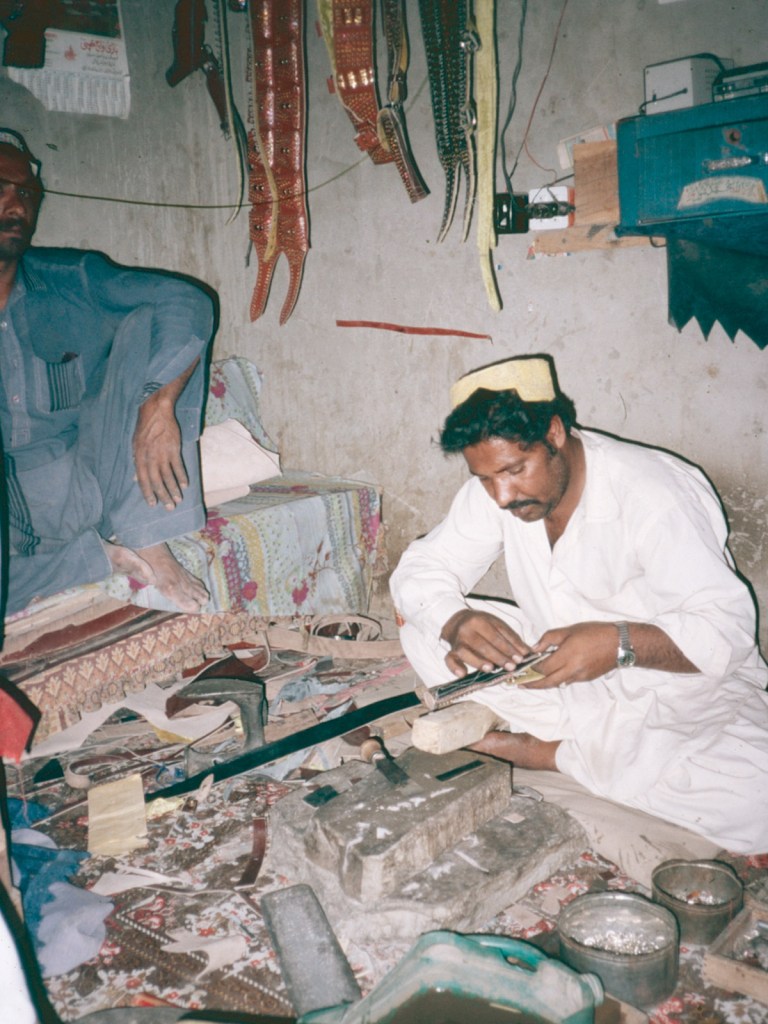

Sheila went shopping most days and had time to explore the bazaars and the local crafts – from sandal-making, to gold and silversmithing. Alone, and in the company of the driver, Janmohammed (ex-Omani army), she made lots of friends and recorded the local crafts in great detail. Janmohammed also took her to many villages, including his own, Ginna, to find out more about the local way of life.

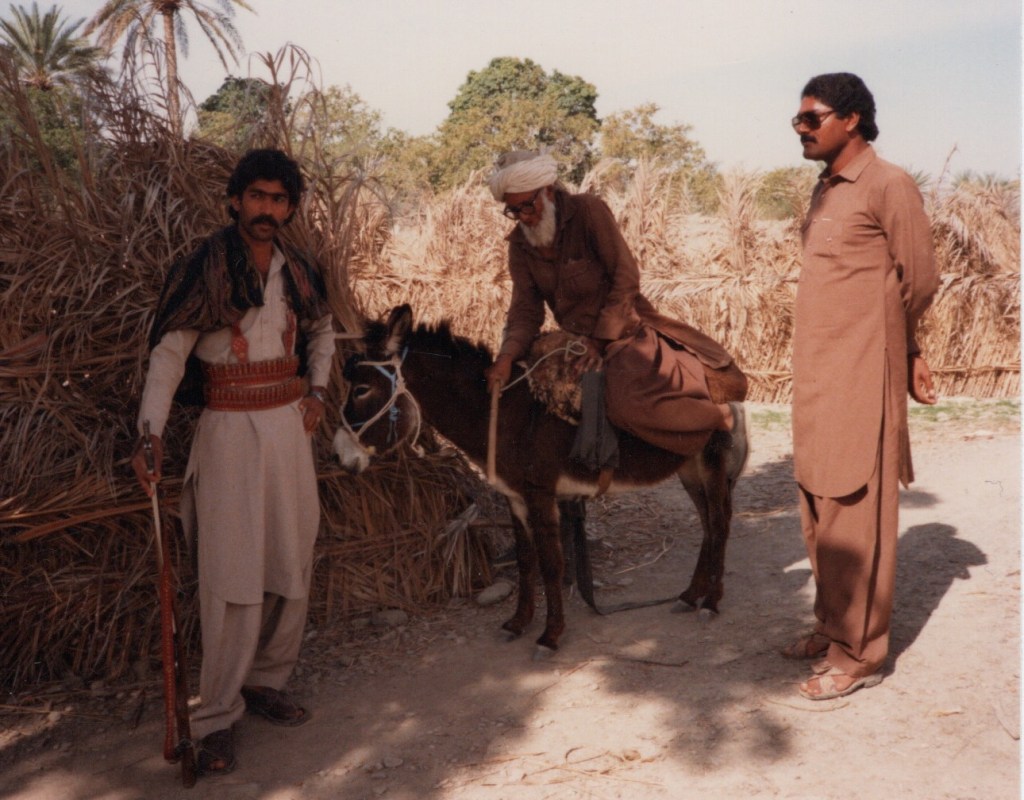

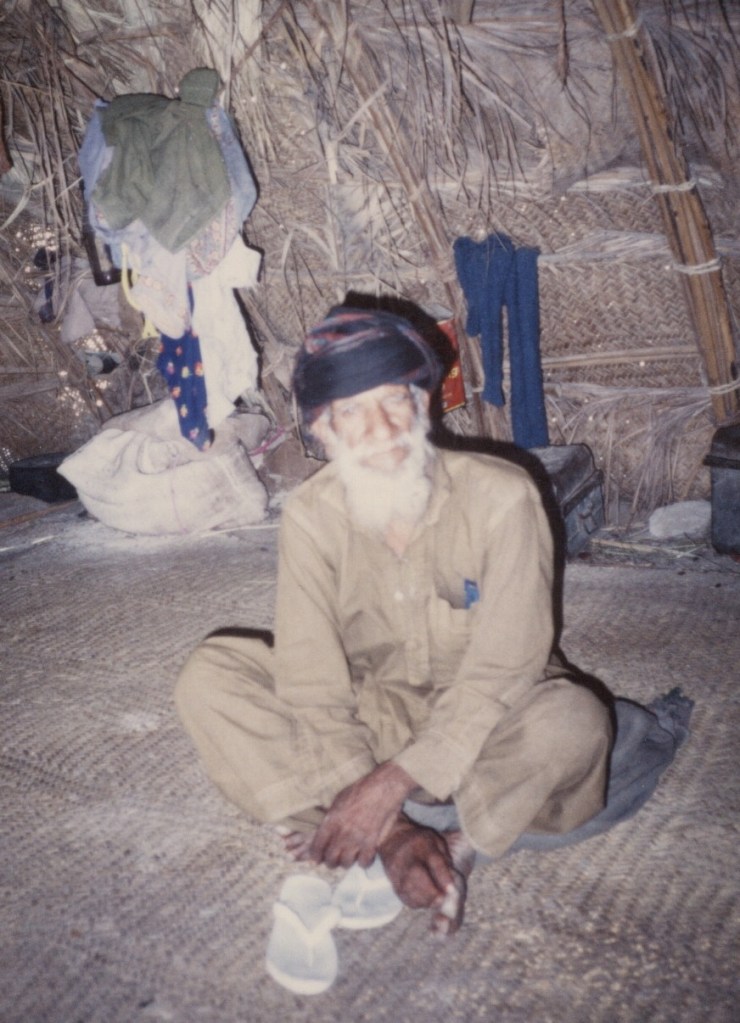

Ginna scenes – the mosque, interior showing suspended ‘best plates’, suspended cradle, the mosque gate and the high street, traditional bed in courtyard, Janmohammed (right) and his donkeys

Gwadar

She was keen to get to the coast as part of her Indian Ocean studies. Finally they were allowed to leave for Gwadar, a rather hairy drive which involved getting stuck on a river and having a puncture, the drive through ‘ an unbelievable moonlike landscape, caused by water flowing over soft rocks. The road followed a river course and Janmohammed said several cars and lorries had been washed away here last year and people drowned’.

The rest of the journey was uneventful – high rocky hills loomed, we skirted over rocks, and eventually reached Gwardar, on an isthmus of flat land, sea on both sides and cliffs behind, like a hammerhead surrounded by sea.

Sheila felt quite at home here, despite the armed guards, and enjoyed visiting the fishermen and boatbuilders.

We wandered down to the fish market and to the shore where the night’s catch was being auctioned – numerous small sharks were among the fish and one beautiful spotted ray. A lively late middle-aged woman wearing heavy gold earrings and ornaments greeted Janmohammed with great affability. She’s in the fish business – and judging by her jewellery is doing pretty well.

…Many boats were drawn up, all had outboard engines and people were untangling and folding nets, repairing them or just sitting around watching other people work. It was a lively and busy scene. Some boats were being offloaded with the aid of cart drawn by two donkeys. Many dogs skulked around looking for food – in the main they look pretty well nourished, lots lying around on the sand or playing around and fighting. Old and needy people quietly, timidly and determinedly pleading for money. Everywhere fish in heaps on the sand awaiting auction.

The larger ones were split and drying in the sun, shark sailfish and other large kinds, smelling frightfully. These will be sent to Karachi to be put in tins, we were told. I couldn’t see why anyone should bother to tin or to buy something with such a dreadful smell. I think they get sent to the Far East

She was thrilled to find big dhows which ‘sailed the gulf, to India, to Arabia and even to Rangoon, but not to East Africa.’There was also an Ismaili community, who kept themselves to themselves, but provided health and education services in the poverty-stricken area.’

There was a bustling bazaar, with a firewood market complete with camels. In a nearby village, Sur, they met a recently arrived camel train which had brought brushwood down and would return home laden up with fish, salt and commodites unavailable in the hinterland.

This area used to belong to Oman, and 8000 Baluchis are employed in the Omani army, with three flights per week. Sur is a transit camp for these men. after 10 years they can opt for Omani citizenship.

By this time the team was beginning to suffer from increasing arguments and ill health; unsurprisingly tummy trouble affected them all – ‘ at the moment of crisis you feel you will never be able to eat again let alone recover’ – and mum had a bad back as well. So it was with some relief that the expedition came to an end after five weeks…only to return in 1989/90!