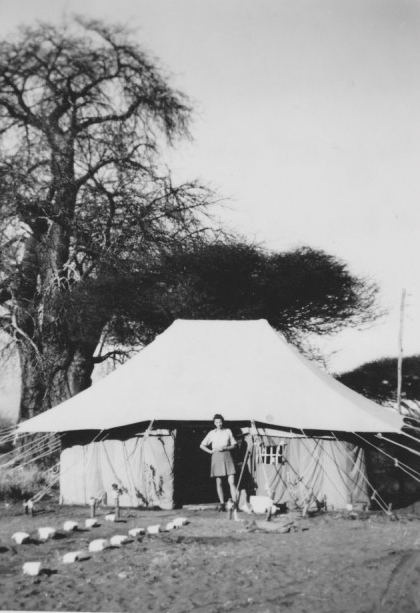

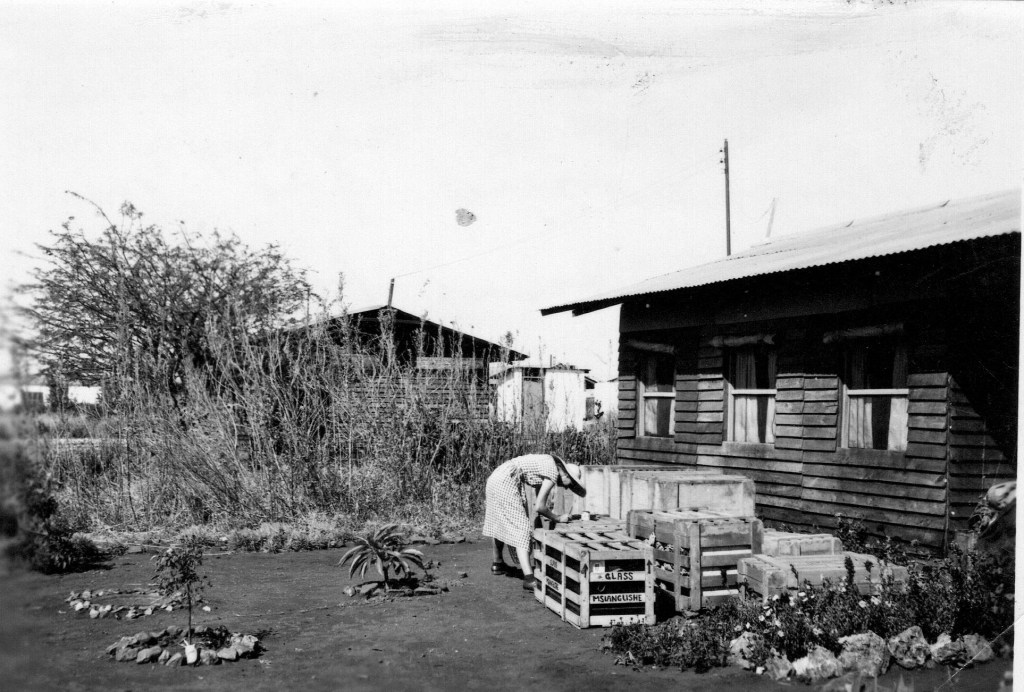

Mum & Nelson, looking out from their hut, Unit III, Kibumbuni

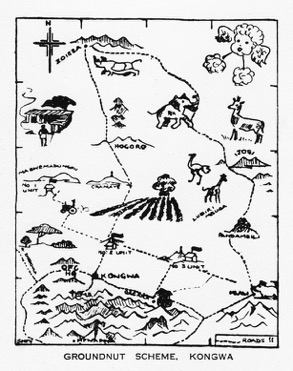

In 1947 the Labour government launched a plan to grow peanuts in Africa to supplement the post-war British diet. Millions of acres, mostly in Tanganyika, were to be cleared and it was anticipated that this would produce 800,000 tonnes by the early 1950s. This was the infamous Groundnut Scheme, which my parents joined in 1947.

It was to be an utter failure which ultimately contributed to the fall of Attlee’s government in 1951. It was short on detail – only mentioning that ‘hugely mechanised forms of agriculture’ would be used – in reality converted Sherman tanks, with ploughs attached on either side to form an enormous bulldozer, named Shervicks, which were still not strong enough to cut though the rock-hard soil, baobabs, and rock.

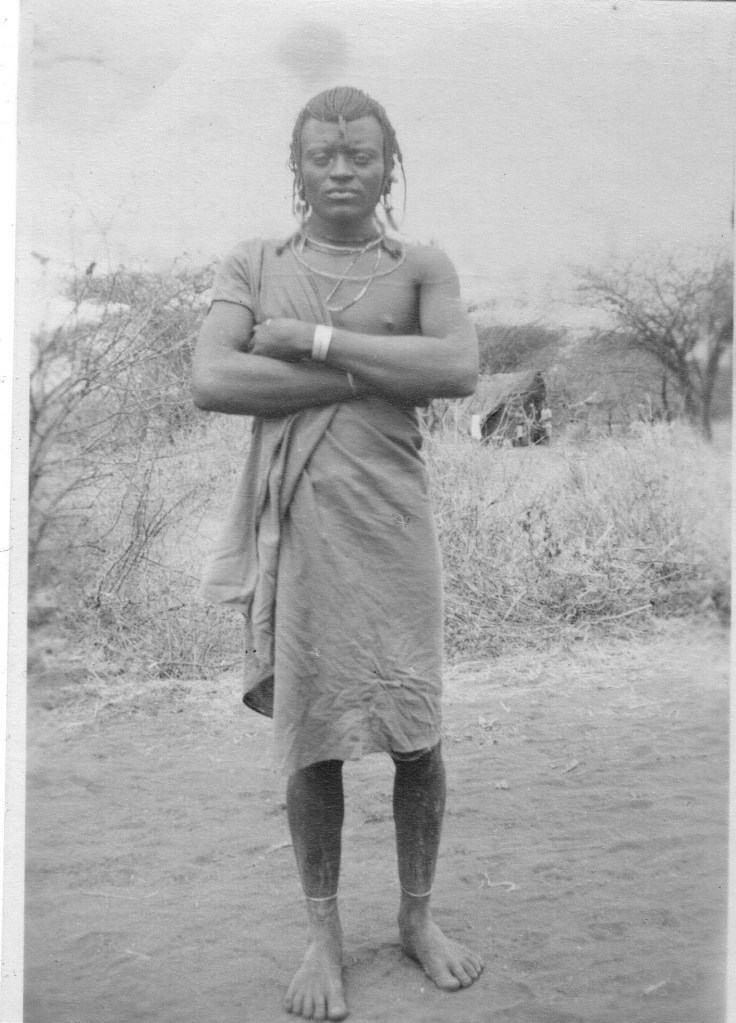

The capital cost was £24m – which had escalated to £50m by 1949 – and 25,000 Africans had to be recruited along with 500 Europeans to start with. There is a chapter on the Scheme in my book The Boy from Boskovice: a father’s secret life.

Here my mother describes her first impressions of Kongwa:

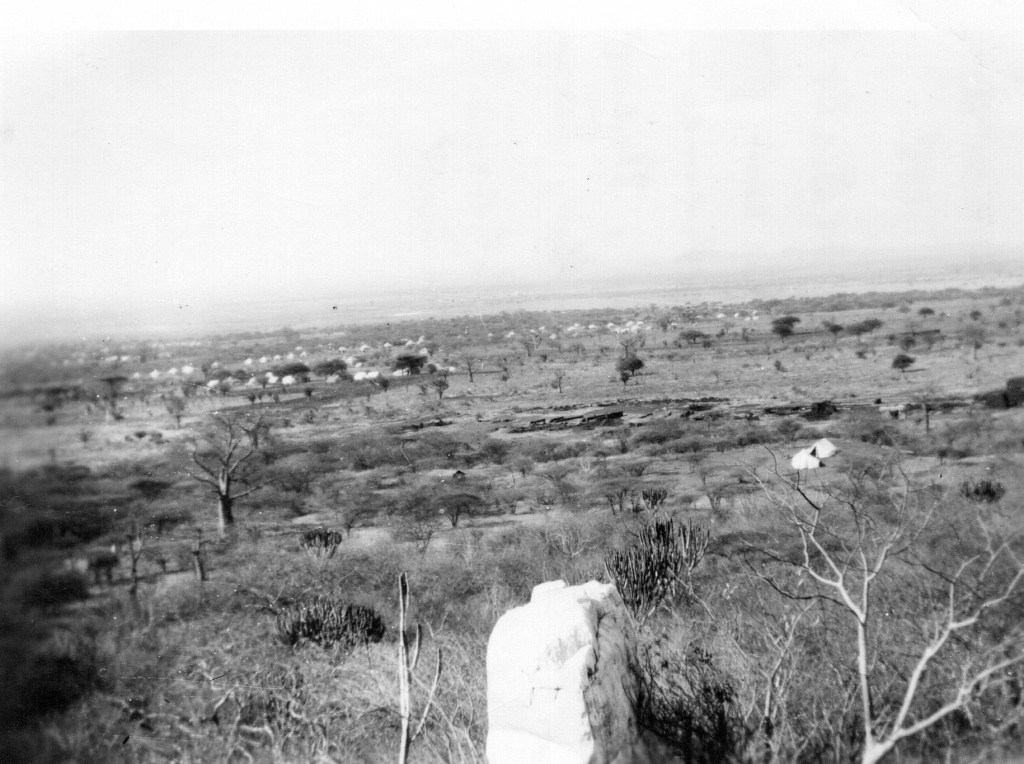

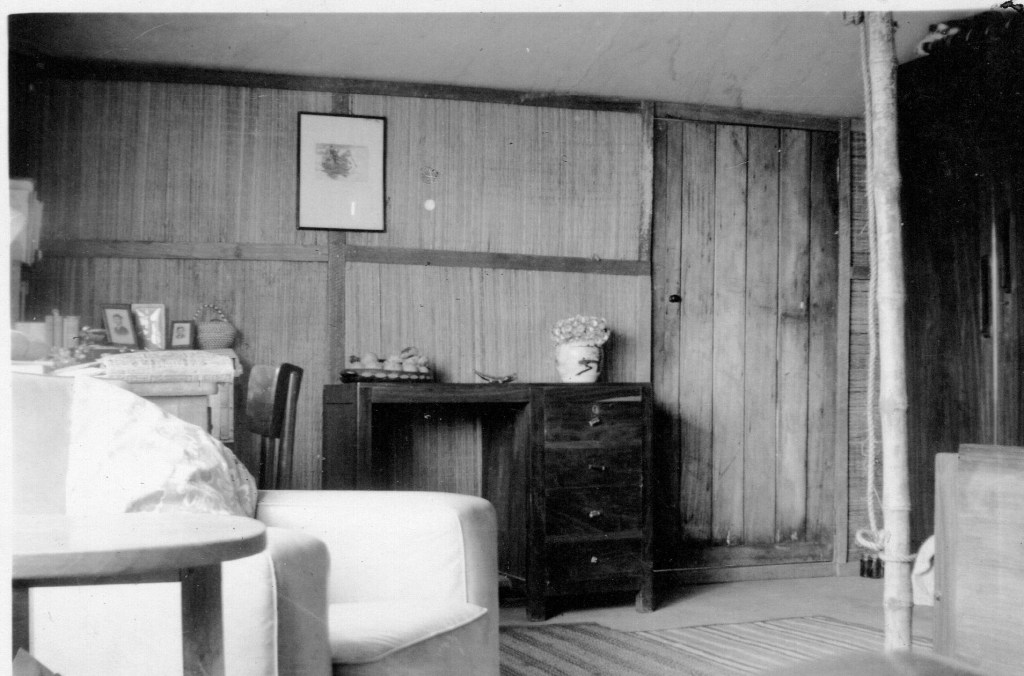

What roads! Sandy + incredibly bumpy + dust, dust dust. It is now the dry season here + the wind blows (as it is doing now very hard) + loads of thick red dust envelops everything, and it’s impossible to keep clean at all! The camp here at Kongwa is situated in the scrub with most picturesque hills all round covered in trees. To the north is a wide plain, where the first Units are and beyond this – some scores of miles away – more hills, blue in the distance. Tom + I have a large tent between us, with a concrete floor – complete with 2 beds, wardrobes, 1 dressing table + long glass + easy chairs, + 4 folding chairs, 2 bedside tables, bath and washstand, to say nothing of mats on the floor.

The tent has little windows which fold open or closed and we have a primus type of lamp to light up at night. Electricity will come soon, we hope – but will now be further delayed for us because the generator exploded + caught fire last night – so that everyone has to use lamps at the minute…There are 3 messes – we are in the medium one (No: 2) together with the other girls + a selection of males. Food is good + plenty to drink. Lavatories are holes in the ground at the minute, but tactfully disguised in little thatched huts.

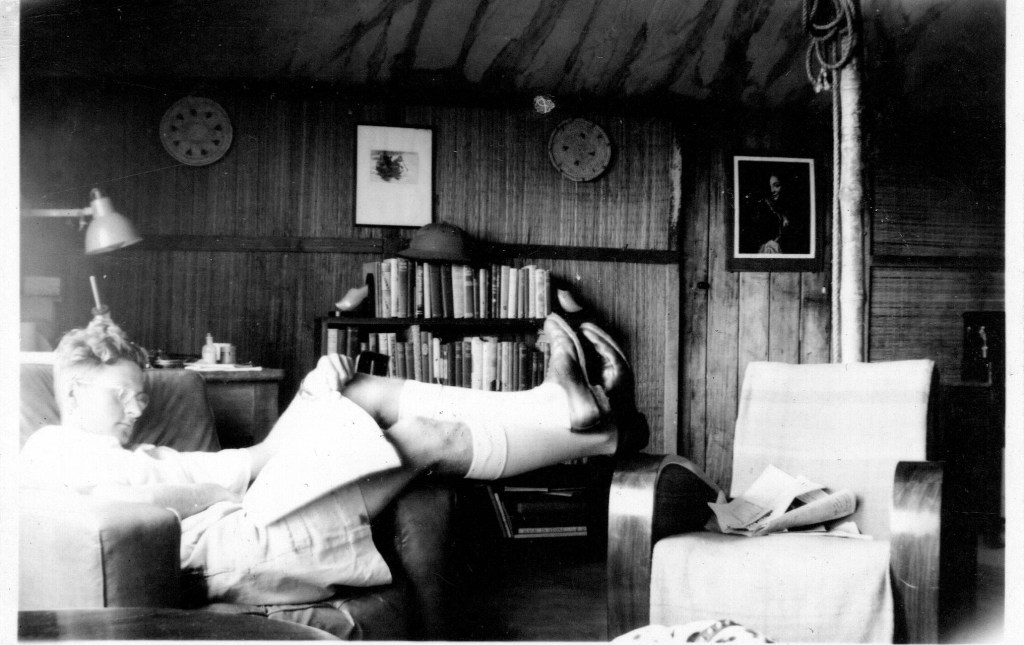

My father, a socialist and trained in agriculture, had high hopes for the altruistic motives of this new venture. Overnight he became a tractor driver and peanut planter, in the most difficult conditions. The ground had not been properly surveyed before the plan was launched and was mud during the rains, and rock hard for the rest of the time. No wonder only pastoralists had ever used it, and they shared it with wild animals – elephants, lions, zebra, giraffe, etc. which they came across when clearing the bush. A pair of sleeping lions frightened the labourers almost to death, ‘Oh sir, we have seen a frightful sight – lion!’ and refused to continue working.

They lived in various units around Kongwa until 1950 when, after a home leave, they moved south to Nachingwea. By this time there were questions about the Scheme and the agriculture minister John Strachey had been accused of misleading Parliament.

They realised it was time to leave, but job opportunities locally were difficult and they had debts that would need to be paid off (for their new car, brought out from England for example) and pensions to be sorted out. Dad was so desperate he even tried to be made redundant. As it turned out my mother’s old boss, the District Commissioner in Kongwa, put in a good word with the Colonial Service and so began a new chapter in their lives.