Sheila first went to Lamu with Neville Chittick, the Director of the British Institute for Archaeology in Eastern Africa, when he was excavating Manda and Pate in 1965 and later they bought a house there, Pwani (sea) House, looking over the waterfront but set back slightly. In the Nairobi and Dar pages I recount my first unwilling visits there but, later, as I became a teenager and Lamu became hippy central, I grew to love it – smoking weed on the dunes behind Shela, while my mum socialised with all her local friends.

One of the great disadvantages of going to Lamu with a mother who was broke was the terrible journey from Nairobi – first by shared taxi to Mombasa (normally an old Peugeot 404, stuffed to the brim with people and baggage)

and then by bus along the dangerous coast road via Malindi, where buses were frequently attacked by Somali shifta gangs, although the bigger danger was getting stuck and stranded in the black cotton soil – as here!

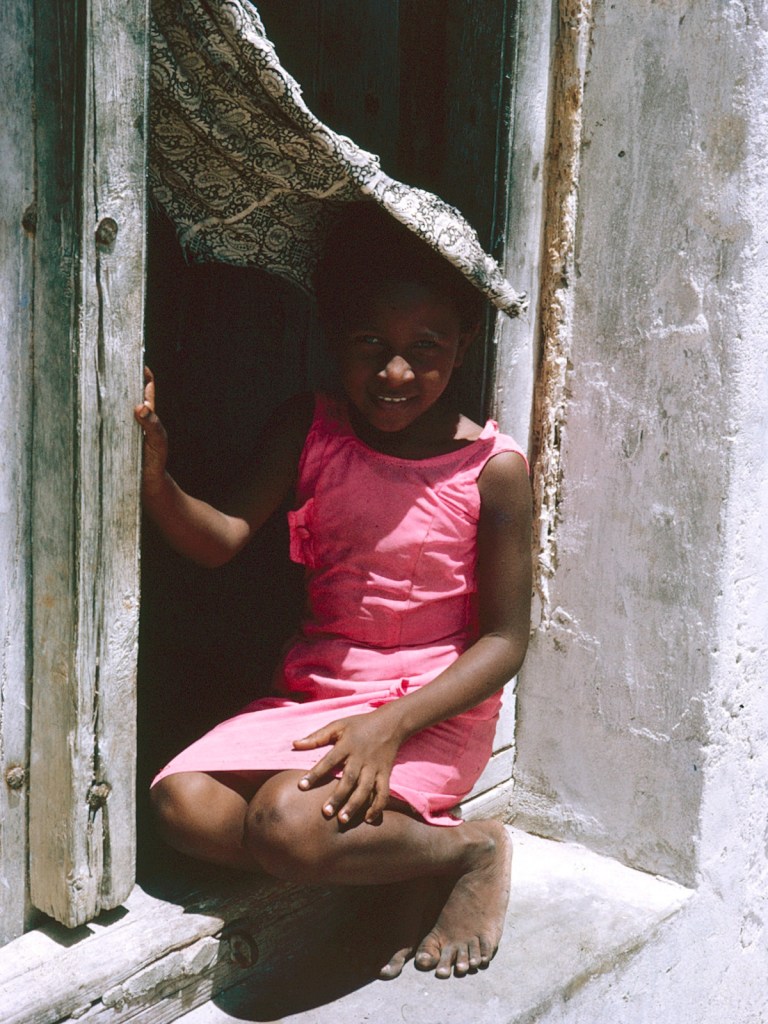

She finally sold the house in 1990 when she felt she could no longer look after it properly from a distance. The few remaining diary entries that follow show the life she had – and loved, despite all its frustrations – in Lamu. She was known a Mama Sheila and when I return there are a few old people who remember me as ‘toto ya Mama Sheila’ – Mama Sheila’s child.

The house at various stages in life – the roof garden was a very late addition

The terrible Lamu fire which narrowly missed Pwani house, seen here with rubble in front of it

This is her final diary entry of her last visit to Lamu in 1990 as owner of Pwani house.

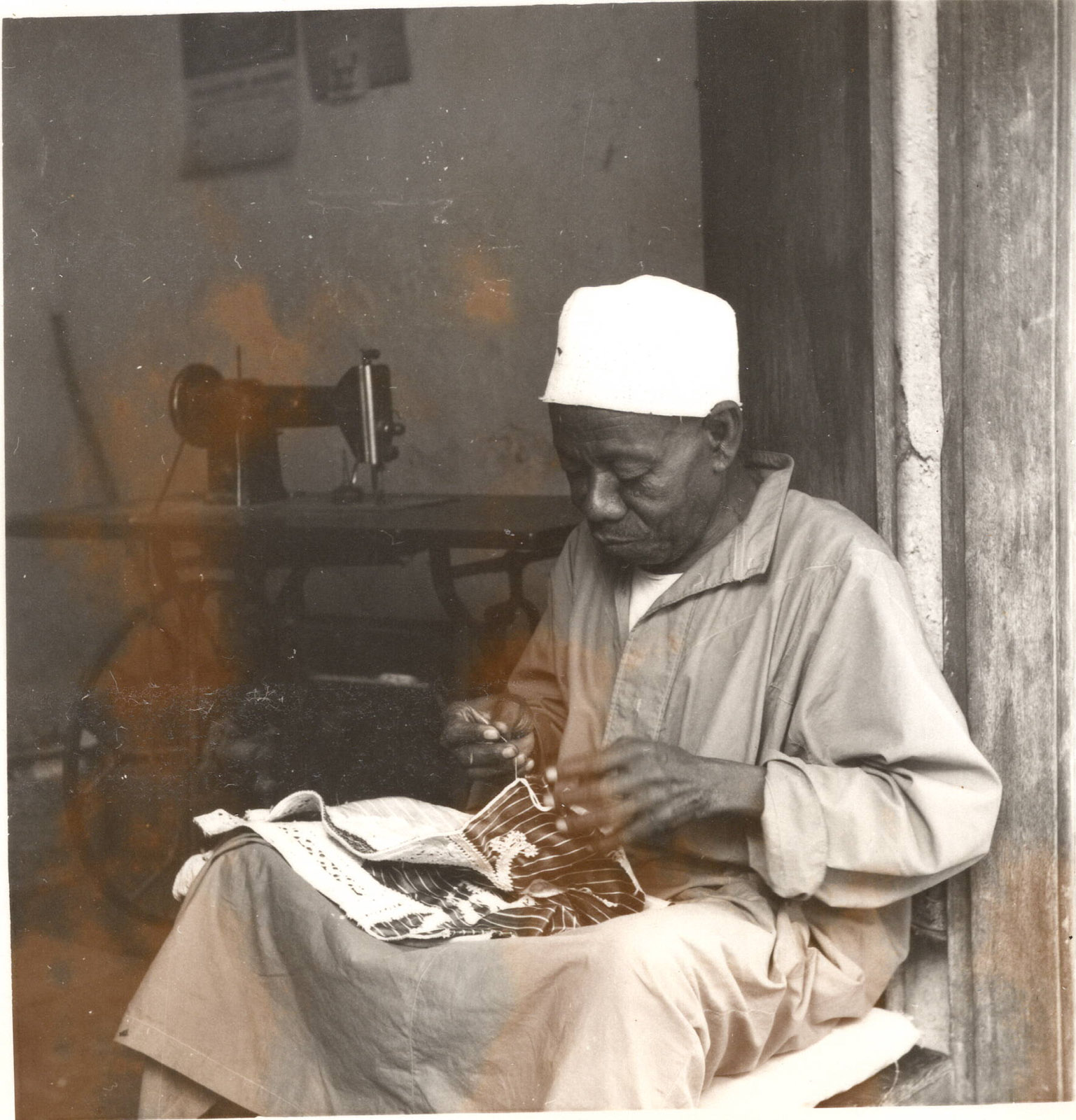

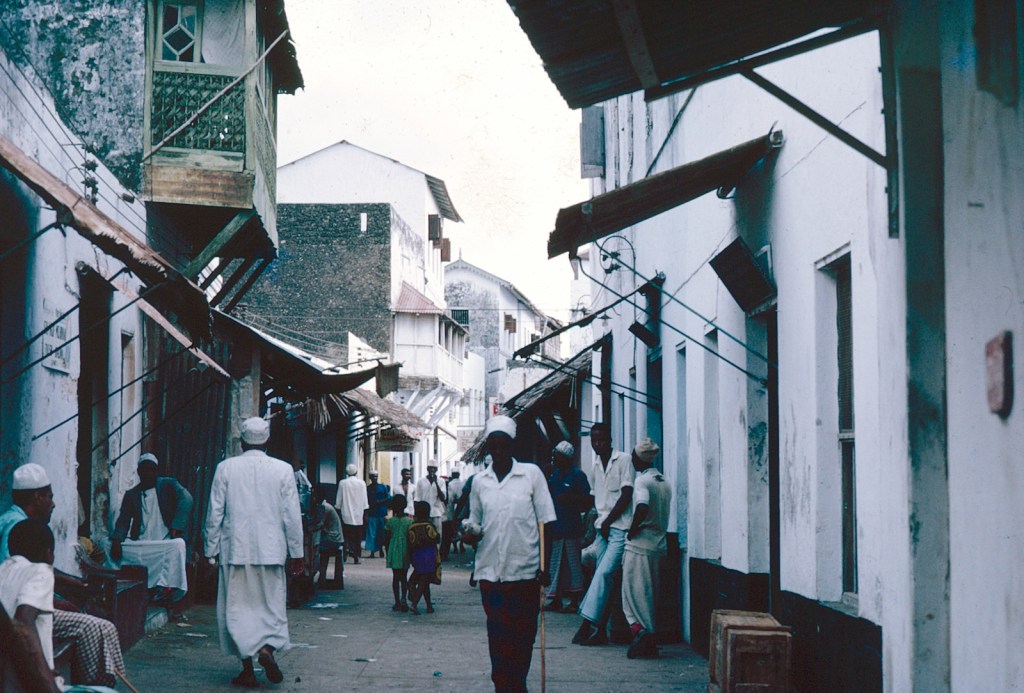

How can I leave this place, I wrote on arrival. Easily and thankfully I can right now. I can only hope the sale goes through and my connections with Lamu can subside into memories of the happy early days when it was clean, tidy and deserted of all of the tourists and no beach boys, no electricity, when locals in kikois and khanzus sat sewing their caps outside the seafront mosque, when the old men congregated for evening chats on benches by the shore and dhows ands boats slipped in and out, silent except for the slapping of the water on their bows and the clunk of coming alongside – and when the evil hand of western civilisation had yet to brush upon the traditional ways of generations.

In the following excerpts and photographs from her diaries, I shall try and give the flavour of the place she loved so much.

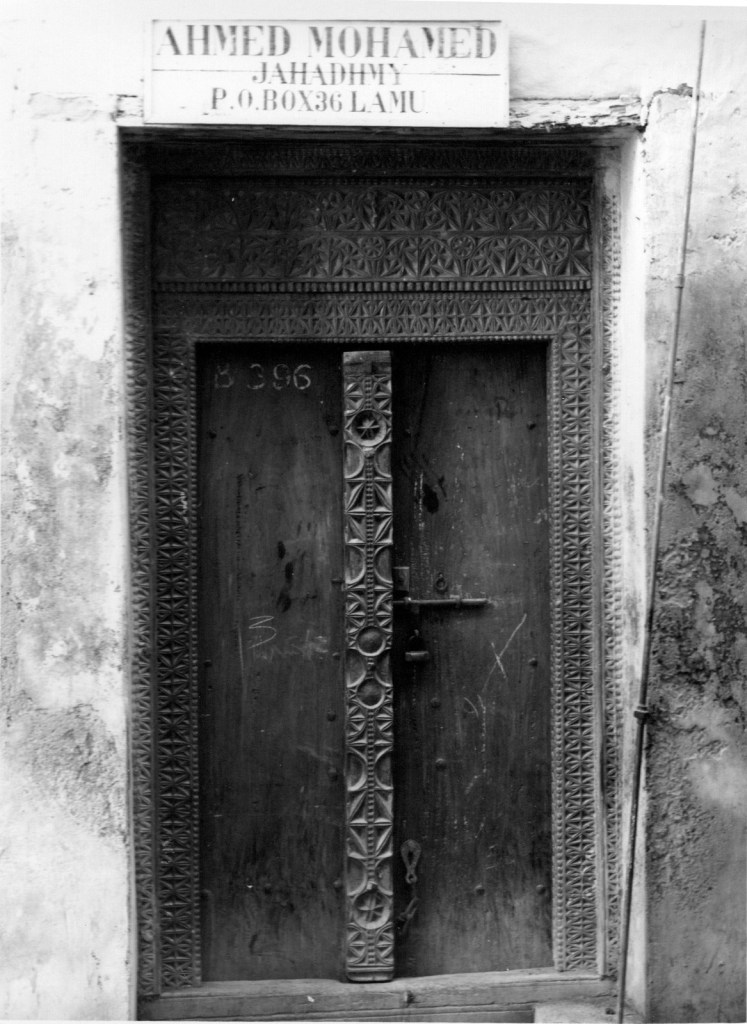

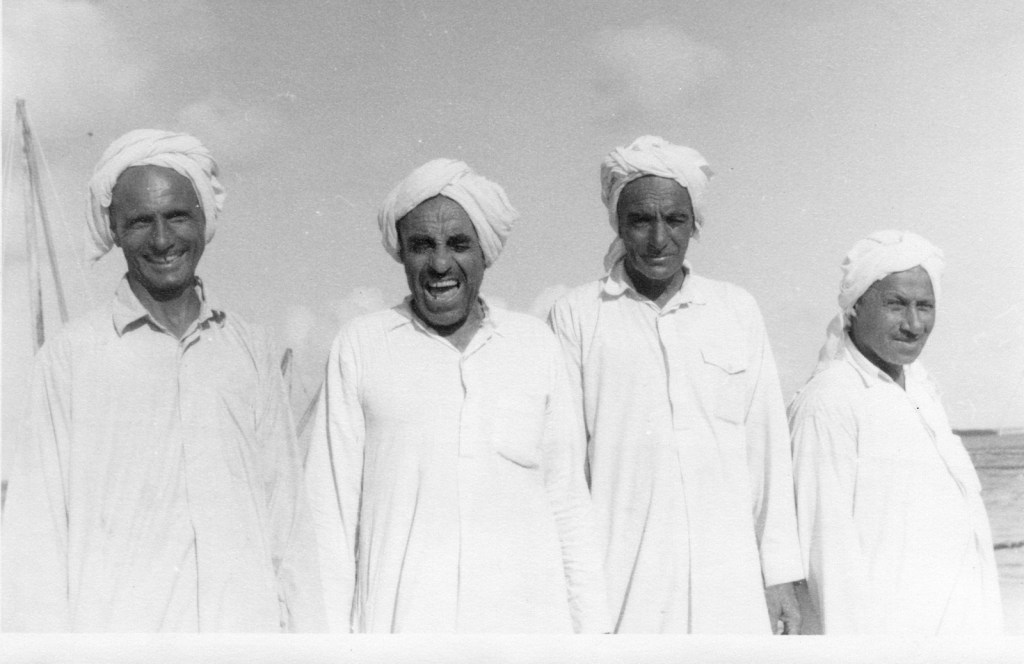

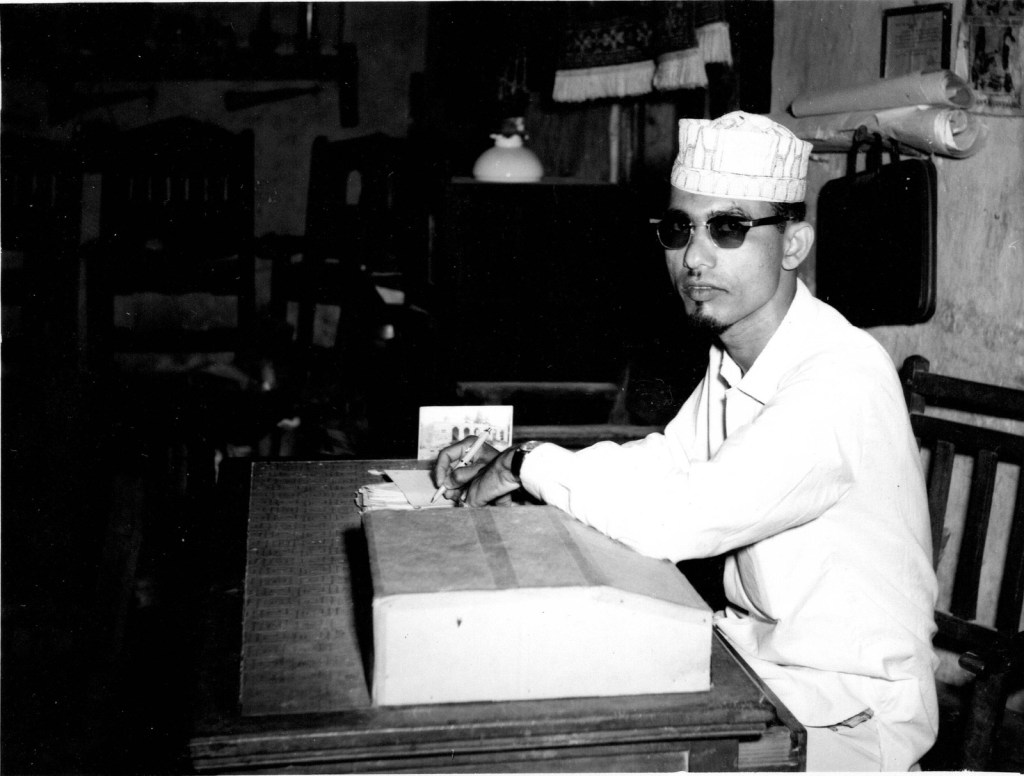

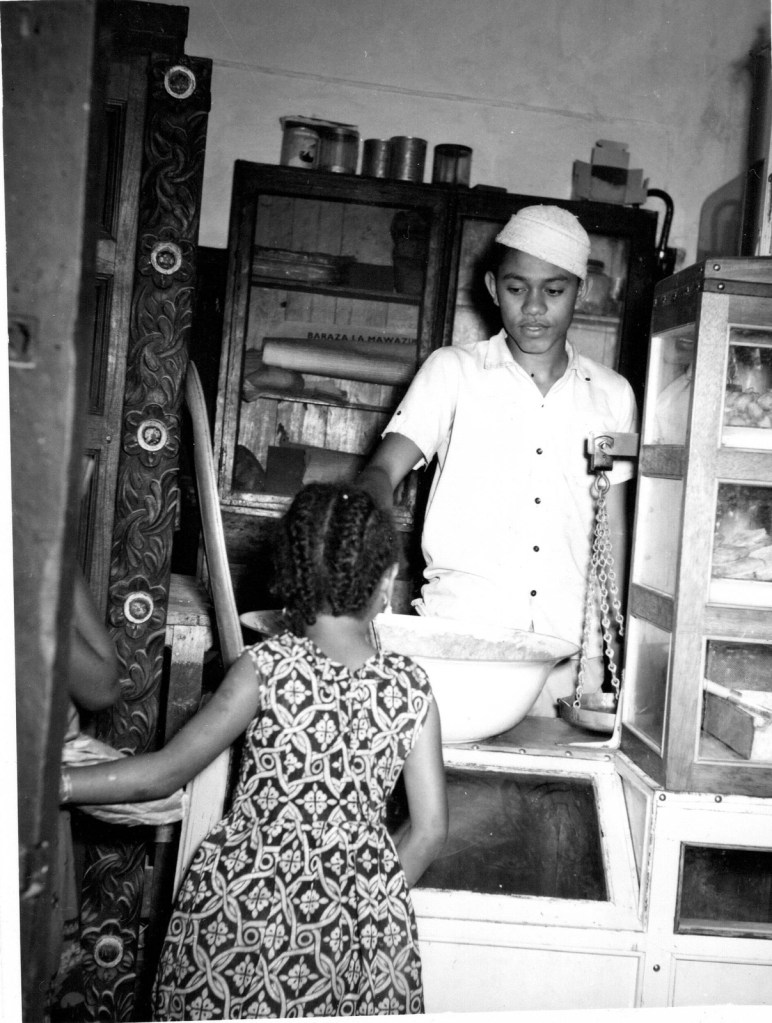

Lamu was living proof of her fascination in the link between Swahili culture and the Gulf, which was fuelled by her Arab chest business and her relationship with Neville. His excavations in Kilwa, Manda and Pate demonstrated these links between Oman and East Africa via the big sea-faring dhows. These dhows (which are no longer in use) used to bring Chinese porcelain, silk, frankincense and spices for the Sultans in times gone by and, more recently, chests, copper, brass, carpets to sell in Mombasa, stopping off in Lamu to pick up mangrove poles for building in the treeless Gulf states; in the past ivory and gold were on the export list as well. I remember seeing the huge stacks of mangroves on Lamu seafront, and the big ocean-going dhows as pictured below, in 1974. The Omani dhow captains, resplendent in their white robes and kufias, often had wives and families in Lamu.

Mangroves being stacked ready for loading on to the dhows

The Maulidis

Sheila was always thrilled when her visits coincided with a Maulidi. Maulidis are an annual event held to celebrate the birth of the Prophet. In Lamu the festival is taken very seriously with groups from far and near gathering to sing and dance. The photos here are from 1974, but the descriptions are of several Maulidis she attended in 1985. Ross and I were lucky enough to be in Lamu in 2022 for the Maulidi. I write about it here and it’s interesting to compare my photos with Sheila’s below. It was obviously much less commercial in her day, and the Maulidis were a succession of events at different mosques, with the children’s, women’s and men’s event all separate and taking place over several days.

Her partner in crime was her agent’s wife Nana, and her two sons who would accompany her. Sometimes Kombo, the agent would as well.

We walked from Nana‘s house along the most torturous path by the back streets to the mosque. K, the older boy, dashed off ahead by a more direct route and arrived before us, little Abdul Khalim trotted and skipped ahead of us. Mats for men and boys bordered the back of the mosque behind which, separated by a rope, mats for the women, girls and small children. Egged on by the children we chose a place at the front of the women’s section and sat down to wait. It was early but the band was tuning up near the back entrance – microphones were being tested and the throng of young boys, with them the Mwalimu, who I recognised from a previous Maulidi, was marching up and down a switch in his hand.

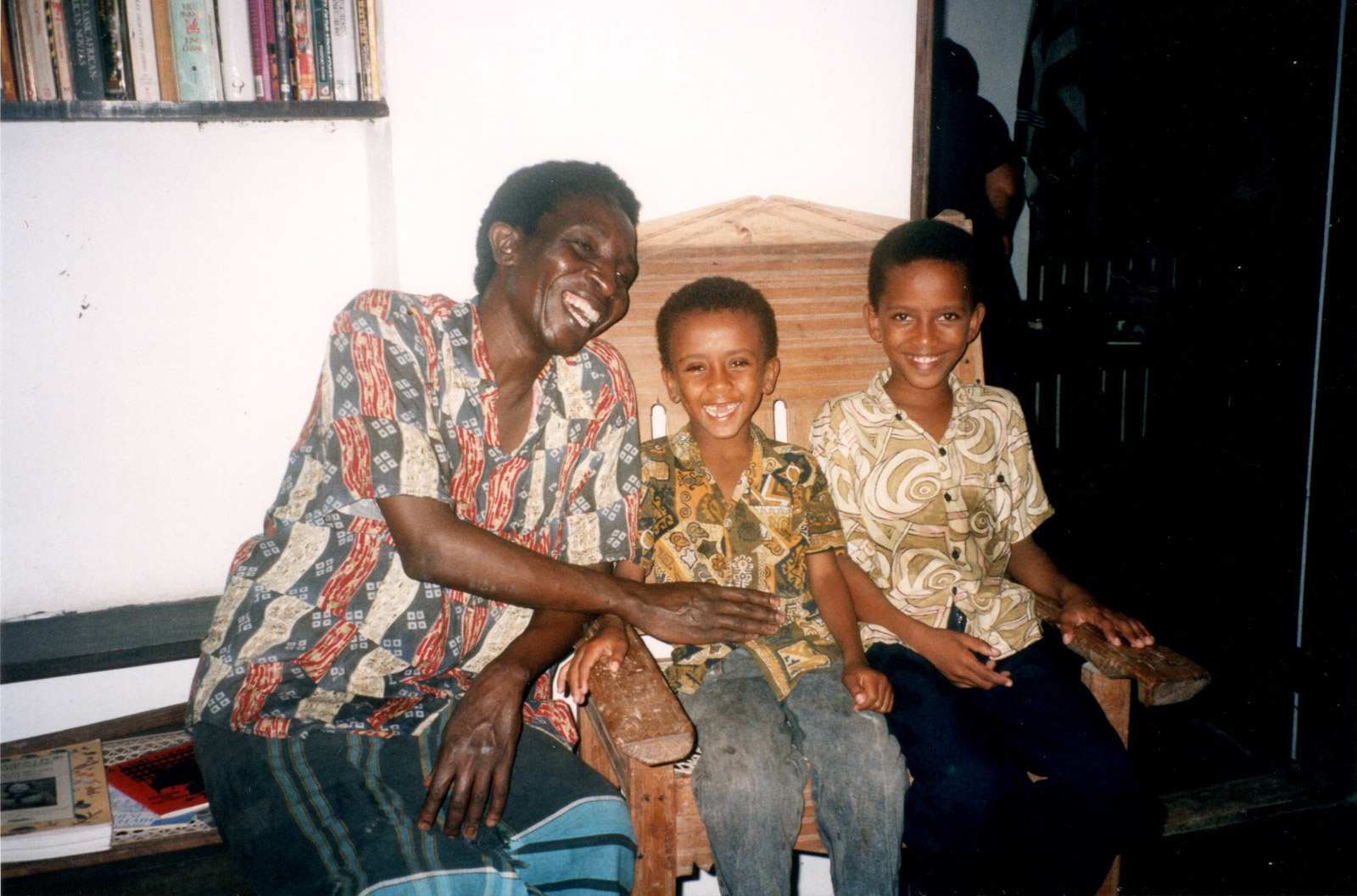

Kombo, Nana and her two boys, K and Abdul Khalim, seen with Ali Maulidi, mum’s faithful housekeeper of many years. They are sitting on my Siyu chair

She would dress up in a ‘long housecoat, with sleeves, made from a pair of khangas, another khanga wound round my hips because of a transparency problem, my head in a scarf, and thoroughly sprayed with mosquito repellent… however, despite my decorous appearance I did not find approval at all. She can’t sit here one of the chief ladies announced severely and tell her she mustn’t sit with her legs stretched out.’

On my evening walk today in the northern part of the town where makuti thatch houses begin to outnumber the stone and the path winds into sand and peters out towards the abattoir – a sad place – and the rubbish dump on the shore beyond, I came upon a small stone mosque where it could easily be seen a Maulidi was about to take place, paper streamers spanned the road, electric light cable stretched from mosque to palm, bulbs bobbing about in-between, and a loudspeaker system was being installed. Yes a Maulidi this evening at 8 pm I was told, but why don’t you join the women who are having their own celebration behind the mosque.

She only arrived near the end, in time to be ‘thoroughly doused with rosewater and wafted with incense’. They were then given small cups of gingery coffee and plates of black sticky halwa were passed around, complete with white paper napkins.

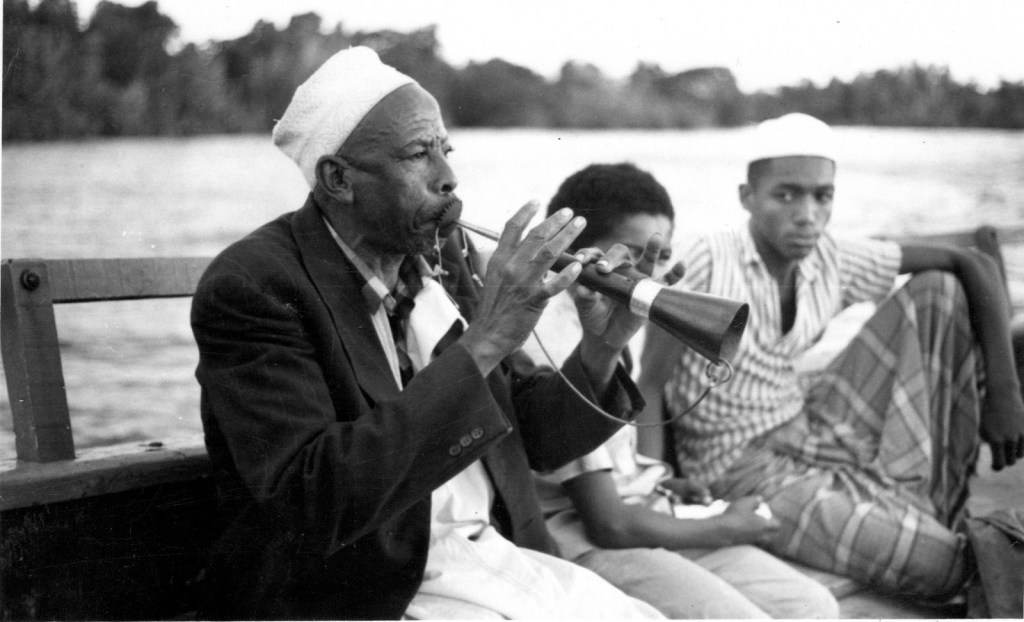

This is her description of the evening Maulidi at the Jamanne Mosque (Men’s Maulidi), which she tape-recorded.

Having ascertained I’d be welcome with my tape, and with the proviso that I be properly dressed, I turned up at about 7.50. The decorations – the flags on lines, interspersed with lights, were waving gaily in the breeze, mats covered the the whole path in front of the mosque and numerous small boys, mostly in caps and khanzus, were sitting around. A band of musicians – flutes, and drums and tambourines – was tuning up against the opposite fencing, and preliminary songs and music started up…

No sooner had the Maulidi started up the opening prayers than the lines of boys in front arranged themselves into two groups facing one another. They then began to sway rhythmically flailing their arms in unison and chanting in shrill voices in response or in chorus with the Mwalimu. Whilst they and everyone else sat, their instructor stood, small stick in hand ordering the proceedings. Anyone who defaulted was called out and put in a place of demotion receiving admonitory taps from the stick. Sheepishly the boy would look to his fellows for sympathy, which he didn’t seem to get.

As the proceedings wore on the boys rose to their feet and began dancing in a frenzy still keeping in unison. The music was lively, the flutes trilling their semi and quaver tones accompanied by great bangs from the various drums, carefully syncopated, and rattles from the tambourine. At one stage the flutes seem to be playing Polly Wolly Doodle over and over again and the dancers processed in circle even more energetically.

We all rose for the Marhaba, alas not so tuneful as of old, and then sat and listened to the sermon…I didn’t understand it all though at least it was in Swahili. We were then doused and incensed – I got a whole dollop on the front of my dress and had to be careful to shield the tape recorder…more singing but more subdued and then voices singing ‘Maulidi imekwisha’ – the Maulidi is over. After that cups was distributed, coffee poured and drunk, and halwa plates hands round. No paper napkins though!

The final Maulidi I attended was at the Pwani mosque behind the Mahrus hotel, now a shadow of its former ancient glories, with old windows replaced by metal-framed casements and one or two storeys added to accommodate the guests.

The mosque is a big one and has an attached school for Koranic instruction where, in the mornings, you can hear the little boys chanting their lessons which they learn by rote in Arabic but with little understanding.

Mohamed and I set out for the mosque, no flags or lights or even a loudspeaker. I began to wonder if the Maulidi was really on, but it was and the question was how was I to get near enough to the centre of sound to be able to record it?

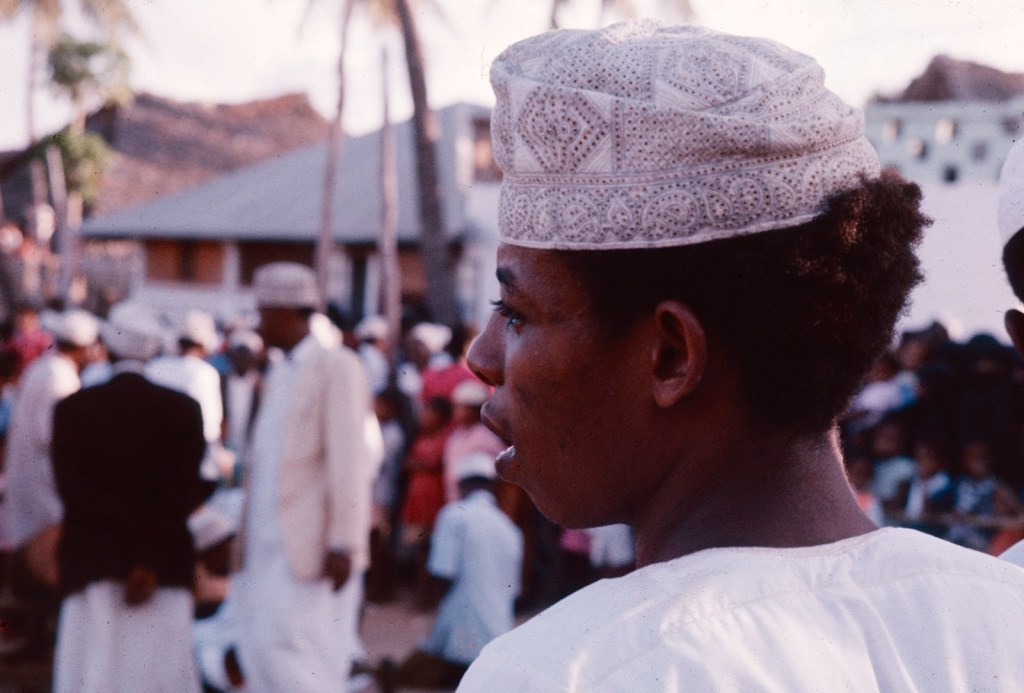

A young boy watching the celebrations, with a cap like the ones the old men used to sew in front of the mosques, 1974

I climbed the steep stairs, was welcomed and given a parcel containing two white and pink khangas with Riyadha Maulidi printed on the message section – a very kind thought as Nana, along with the many other employees of the Lamu County Council, hasn’t been paid for four months

We paced the perimeter and eventually two windows were opened so that I could place the recorder as close as possible to the nearest windowsill. This meant I had to stand in the street to keep an eye on it. Various heads turned to see what we were up to, but no one seemed to mind. I chose the window nearest the Mihrab.

The Maulidi began and I lent against the opposite wall, several other women keeping me company. It wasn’t really at all loud save the beating of the drums and the chatter of the children, the conversations of the passers-by, the greetings to me and goodness knows what else – which will be heard when it is played back and will certainly blot out much of the Maulidi!

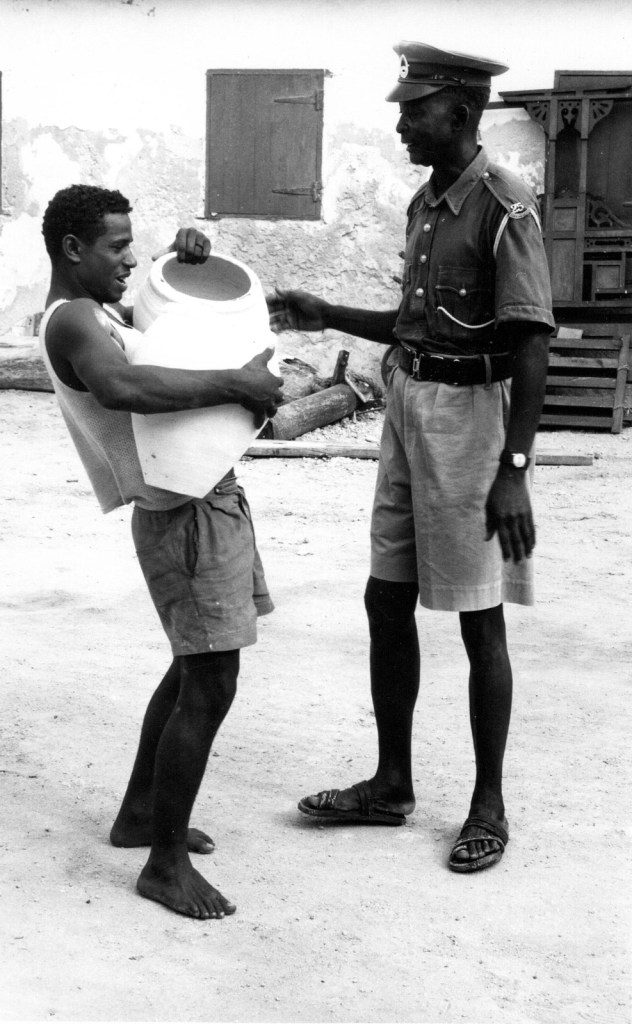

A group of little girls managed to scramble up the wall to look out the open windows and anonymous friend persuaded them to move off, but they were soon back once he’d gone. Bakari Samoibwana stumped and limped up. He’s got one of the loudest voices I know but I managed to get through to him I’d got the tape recording. This meant only that he talked to his friend in the Maulidi through the next window! Bands of small boys kept dashing up with kettles and containers, empty one way, full of water on the return trip, and there was the ever-present shuffle shuffle of pedestrians.

The Maulidi was a short one, no address. Soon kettles of orange were being poured into glasses – no halwa – and the congregation dispersed.

Maulidi dancers with their sticks, 1974

Cats of Lamu*

Lamu is full of them, all shapes sizes and colours. Most of them are miserably thin and uncared for. People tend to dump unwanted kittens near the market where they lie or crawl about and probably soon die for lack of sustenance. You see solitary kittens everywhere, tiny with huge ears sitting huddled up in a place where they will probably die.

Most shops in the main streets own a cat and these are the cream of the Lamu feline world (see photo montage above). I daresay they are quite well fed Lamu-style, with a bit of meat or milk and some leftovers. Anyway they lie or sit on steps, relatively sleek, cleaning themselves or lie among the goods for sale, feeding and washing their babies and presenting a totally attractive sight.

Male cats range around hungrily smelling out interesting females and having fights accompanied by ghastly howls and shrieks – often these are on top of walls or in the waste ground among the houses. Cats of all kinds, colours and sizes congregate outside the Swahili restaurants and hotels seeking mishkakis [kebabs] and when you walk through the streets at the back of the town, you sometimes see terrible sights of bleeding faces, eyes and noses. No one even to lick the sufferer better – once you’re adult you’re on your own in Lamu.

Long ago I remember exploring a derelict house looking for possible bowls in barikas [plaster water storage containers] when I saw what appeared to be a snake. Hastily stepping back and looking again I saw it was a skeleton of a cat, its very long tail seeming to be the snake.

We always keep a cat or two in Pwani house hopefully to control the rats but I saw one to my horror in the kitchen last night. Our cats sadly are never loved but perhaps in a way are respected. Ali certainly feeds our cat and has asked for extra money recently as the price of meat has gone up, but our present one isn’t at all friendly; said to be a she, though really her anatomy is such that she could be a male but I don’t get the chance to look closely. She’s the usual white with tabby patches and has the pretence of being long-haired. Male or female. She doesn’t produce kittens and I should imagine is probably in low health due to worms and parasites, but she’s choosy about food doesn’t like fish, though I did see her delicately trying yesterday‘s rice put outside on a bit of paper, presumably for other less fortunate felines.

The front baraza at the Boma has always had a big population of swifts who dart in and out particularly in the early morning and in the evening, visiting their nests or, when there have been wantonly knocked down by small boys with long sticks, endeavouring to set up house again. This morning I saw a mother cat, her baby sucking, and a male that was his father as they were all ginger, all waiting on the veranda, the mother looking up hoping for casualties, the male more interested in the mother, while the baby just went on sucking.

Heard later that our cat is also a wanderer and follows Ali to his mother’s house near the shore just like Akiba’s cat – see below.

Akiba’s cat

Akiba is an elderly Englishman with the reputation of knowing everything about everyone and therefore to be avoided unless to acquire information. Talking in the street to Leonard Scard the other day, Akiba came up, greeted Leonard and then me as if he knew me well and all about me, and then started to exchange local gossip. He was accompanied by a small cat, slightly fluffy, a dark tabby. This cat accompanies him to market every day where it stations itself by the meat stalls while her master buys her food. If he is late, he told me, she goes off on her own and waits for him there and she can find her way home by herself if needs be. Her name is Mwanabuu, to which she answers. Said to be the child of a former cat which died. Mwanabuu arrived on the scene at this precise moment and took over all the habits and idiosyncrasies of the former house cat absolutely to the letter. Akiba is clearly very fond, indeed proud, of her and I must say I was totally impressed too.

*all photos from my 2022 visit apart from the Pwani house cats

Sheila’s last visit in 1990

My evening saunter had started with the carpenter – he said he’d come tomorrow to fix some stuff on the back veranda which had become adrift; then to the shoemaker; and then round up from near the main street near the house to Kicheko‘s [Ba Allen] old place, bougainvillea dripping from the rooftop, way back to the high part of the western town, first through narrow alleys of old stone houses, twisting, turning here and there, some derelict and empty, others occupied by local people and others yet again having been made into guest houses of all types; some tall and imposing with riots of luxurious bougainvillea spilling over roof and wall, and derelict tambuu [leaves for betel nut] plantations – there must be better money elsewhere – tidy mosques, their doors open, Mihrabs painted violent greens, reds and yellows, floored with mats, clean and quiet. Sometimes they have open spaces walled around, called ziaras, where the congregation sits for Maulidis or important occasions. They’re always swept and clean, often with elderly men sitting around outside chatting, dreaming or sewing Swahili caps.

Then on past the Anisa mosque, with the shining green painted dome in Indian style. It’s in this area that Mohamed Matar bought a plot of land from Ganzel [?]. Why I wonder save that he loves doing deals and being blind there isn’t much else to interest him save his family and the odd bit of fluff who invariably accompanies him in Mombasa.

… back to my evening round I called in to see Ali Maulidi‘s mother who makes and sells posies of jasmine each evening. She was at work, a pretty ginger and white kitten playing at the door, being teased by an elderly shoga [homosexual] who was twiddling a stick. Shogas are totally accepted here. Ali himself is one though he doesn’t seem to have any boyfriend at the moment. Shogas often attend the female celebrations at a wedding being considered safe and they can also play music at such festivities…

… which makes me think of the two transvestites who I’ve known for years ever since they were nice looking young things mincing around in T-shirts and shukas [kikois], handbags and hair slides complete. They lived and still do I think in a little house next to the well of the new mosque, not far from one of my two houses with an entrance by a bridge over the street which I called the Dharaja house. it was subsequently let by the landlord to Pamela Scott who called it after the mosque.

I’ve seen both transvestites since my arrival, both friendly and charming in their somewhat hideous way – they chew tambuu which makes their gums and teeth red and now, probably approaching 40, they look sad and tatty and I don’t think respected, but they are poignantly sweet whatever they look like.

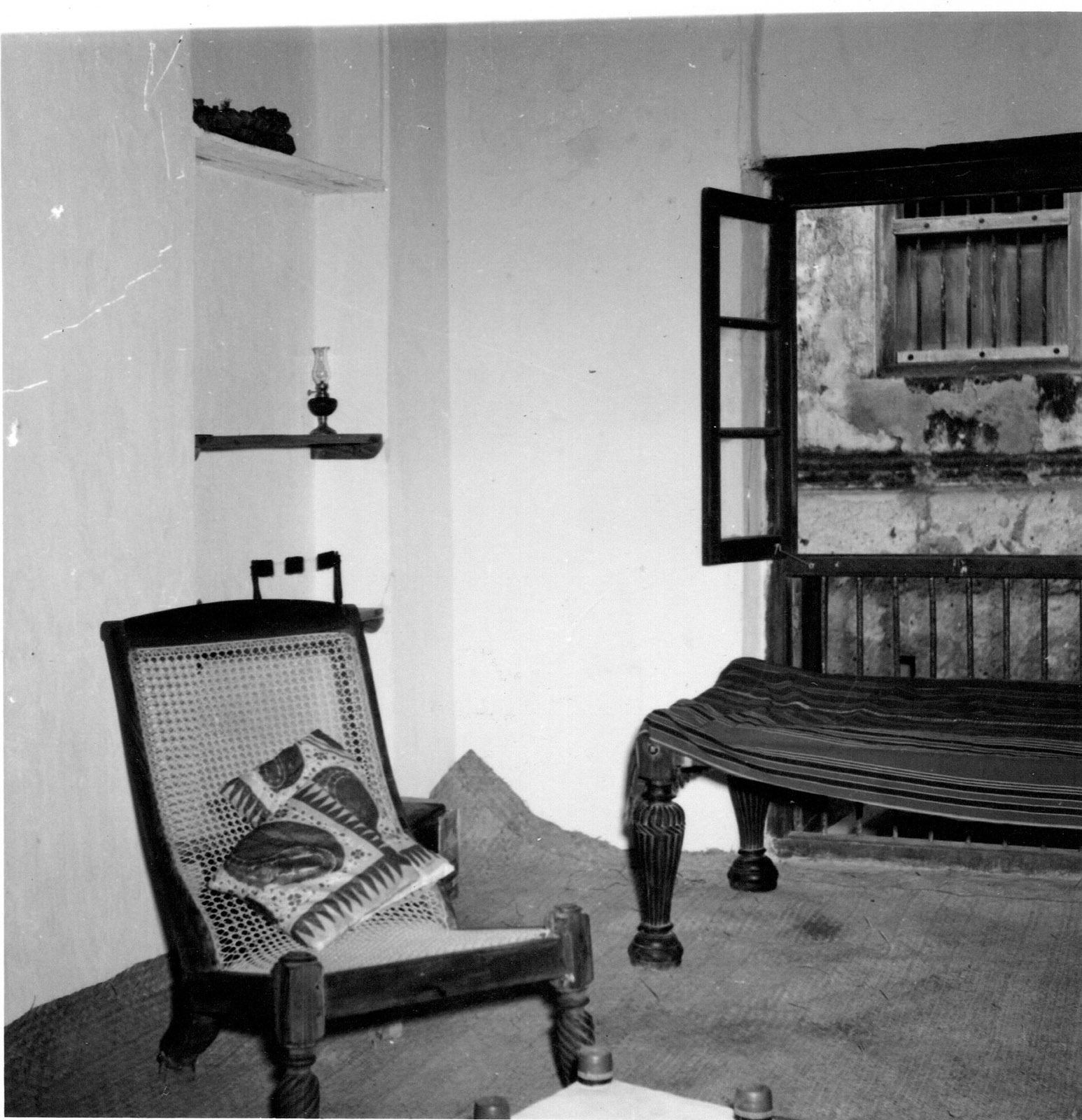

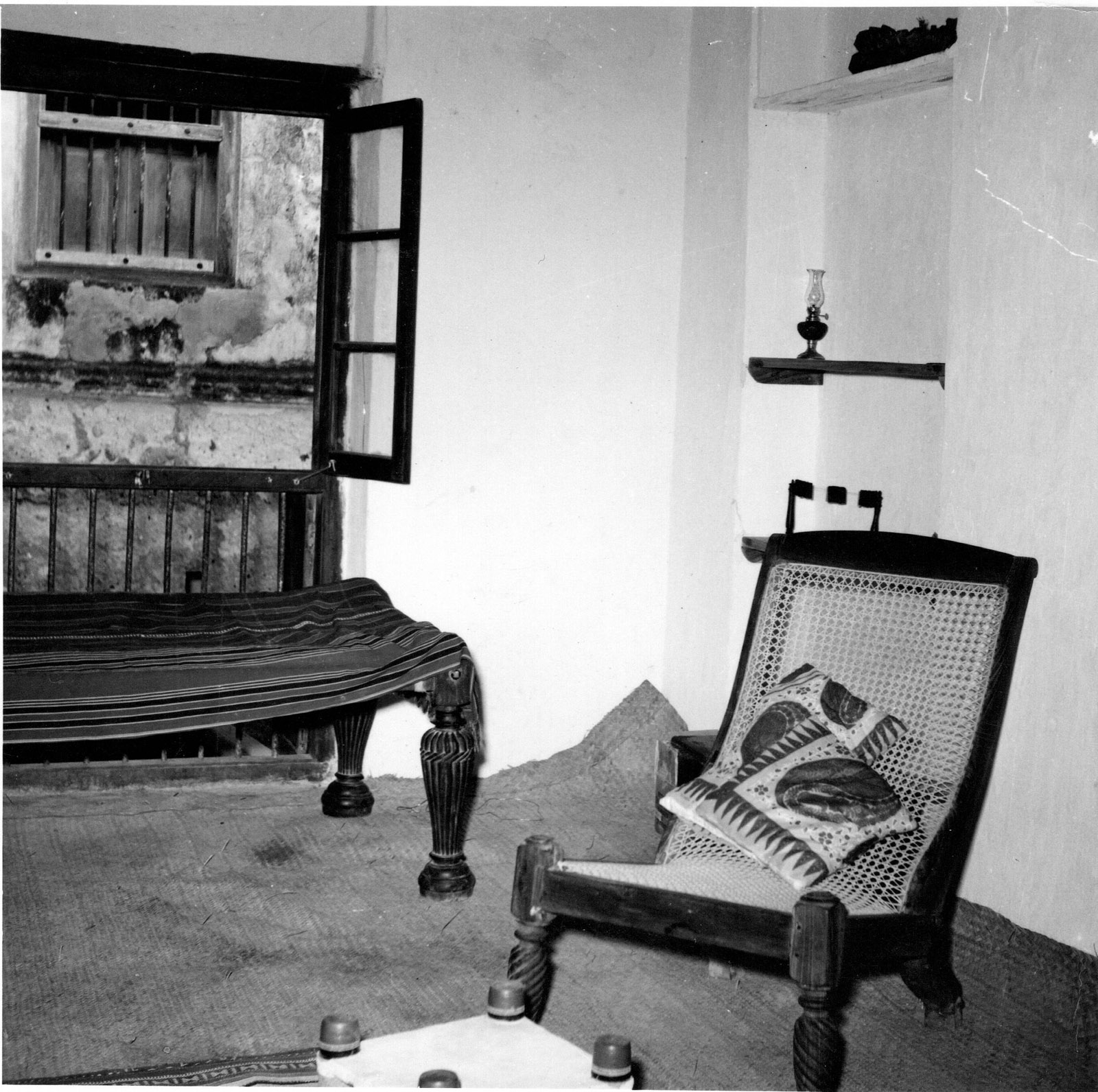

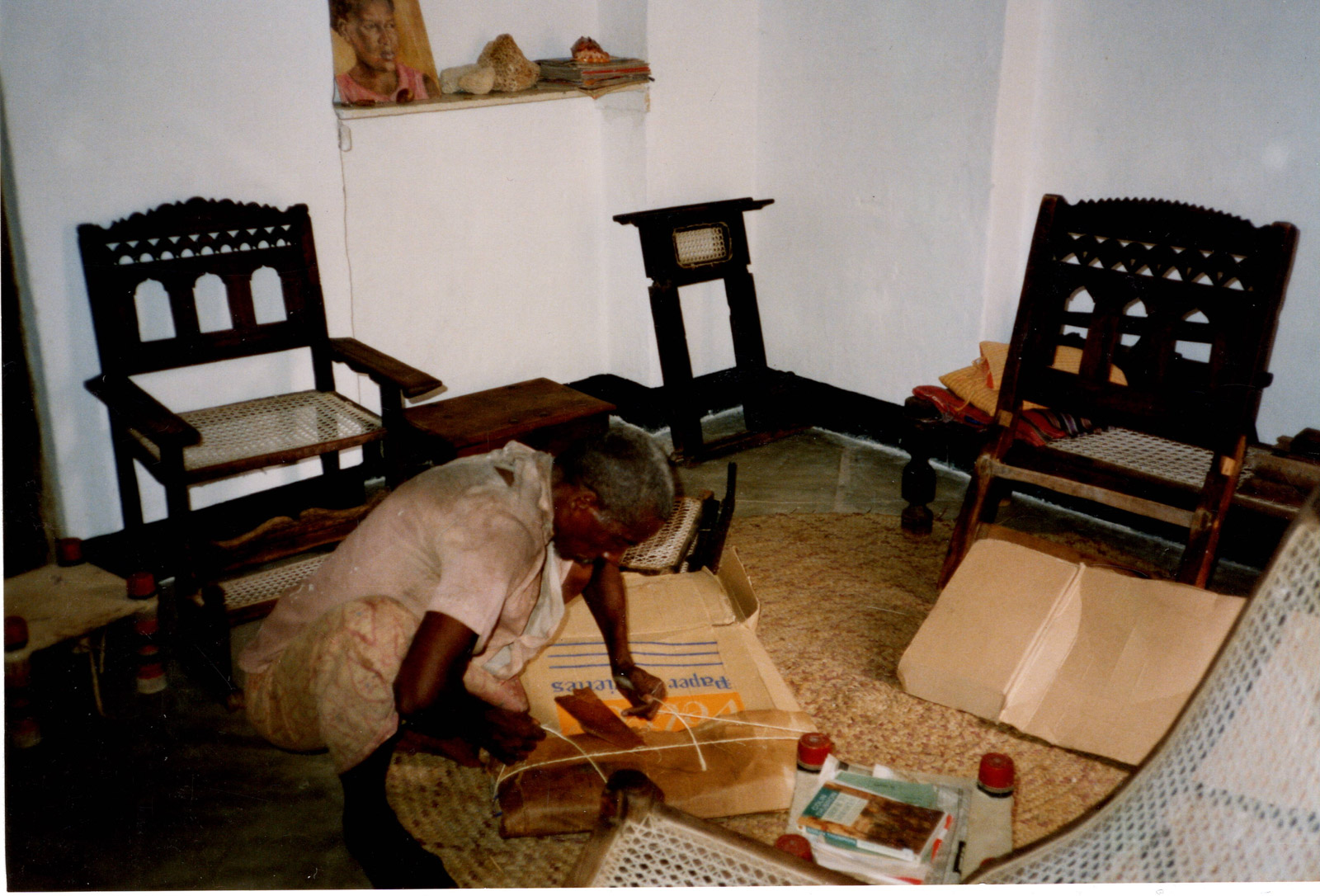

During the late afternoon Basalama came to look at the mpingo chair which I wish to have dismantled and take to England – Vicky would like it. I felt unbelievably sad to see this wonderful chair, black with ivory and bone inlay, latticed with white cord, being taken apart. They will come and do it finally tomorrow but meanwhile it stays in the corner of the room – a chair of authority used at weddings in pairs. There is some connection with Portugal in these chairs. The arms are shaped and cut as old Portuguese ones are, and the bottom rail on which the chair rests is similarly cut and carved. I want to take another chair on which I’m sitting now – it has scrolled arms, also in Portuguese style and is low and comfortable. Somehow I can’t see these chairs in England yet I can’t bear to sell them. Nor can I bear to sell the house. But it is sensible to do so. [Both these chairs are in my home]

Basalama packing up the chairs

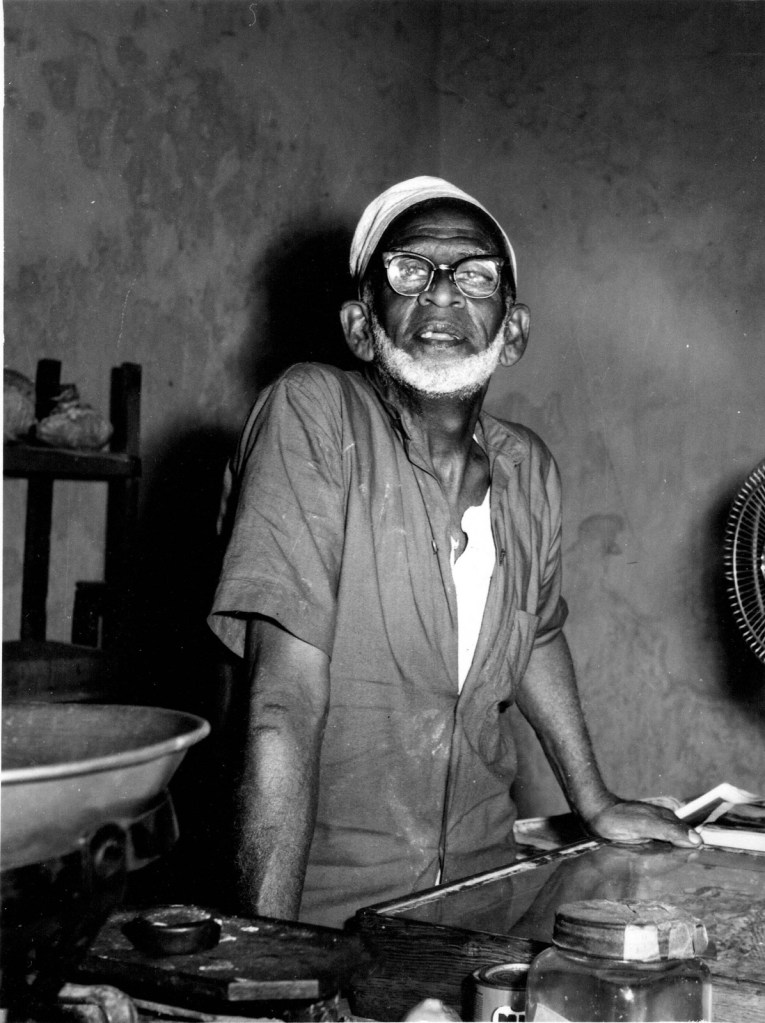

Sheila with her other favourite old man – the waistcoat maker

… Many visitors later, get another knock, this time it is Barosso, himself deaf and bellowing who stumps up the stairs to give me a paw paw wrapped in a piece of newspaper. It is very sweet, he informs me, cut it and put sugar on it were his instructions. He only stays a minute as he has ‘business’ elsewhere. Mariam [his relative] believes he must be over 100 but I should think around 80 is more likely. He’s a well-known character who sells Siwa [horns] to the unsuspecting tourist (he’d to sell anything to anyone and convince them it was what he had said it was). I have known him ever since I first came here over 20 years ago and he really hasn’t changed much.

The trees which are now quite tall between me and Petley‘s Inn have been flowering. First a sweet smell but now it’s fetid and rather unpleasant. Small birds flitter about, kind of sparrow and a yellow and grey type which pipes tweet tweet tweet tweet tweet tweet in a melancholy strain.

Talking wildlife, we disturbed a rat yesterday when we were investigating a pile of old furnishings downstairs. It scuttled about and I screamed, rushing to Ali‘s nearby bed where I sat with my feet up whilst he thrashed about trying to kill it. Eventually it hid under our cupboard beneath the stairs. Ali had the bright idea of pouring hot tea from a thermos which flushed it out and, poor thing, he dispatched it, but you can’t be doing with rats.

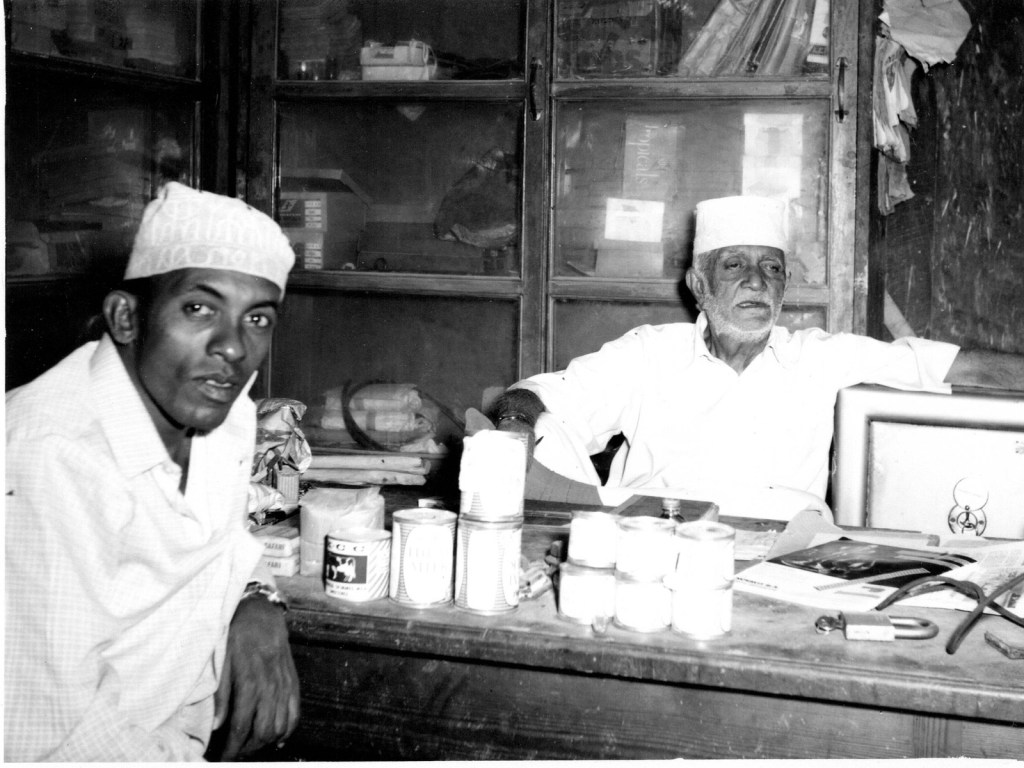

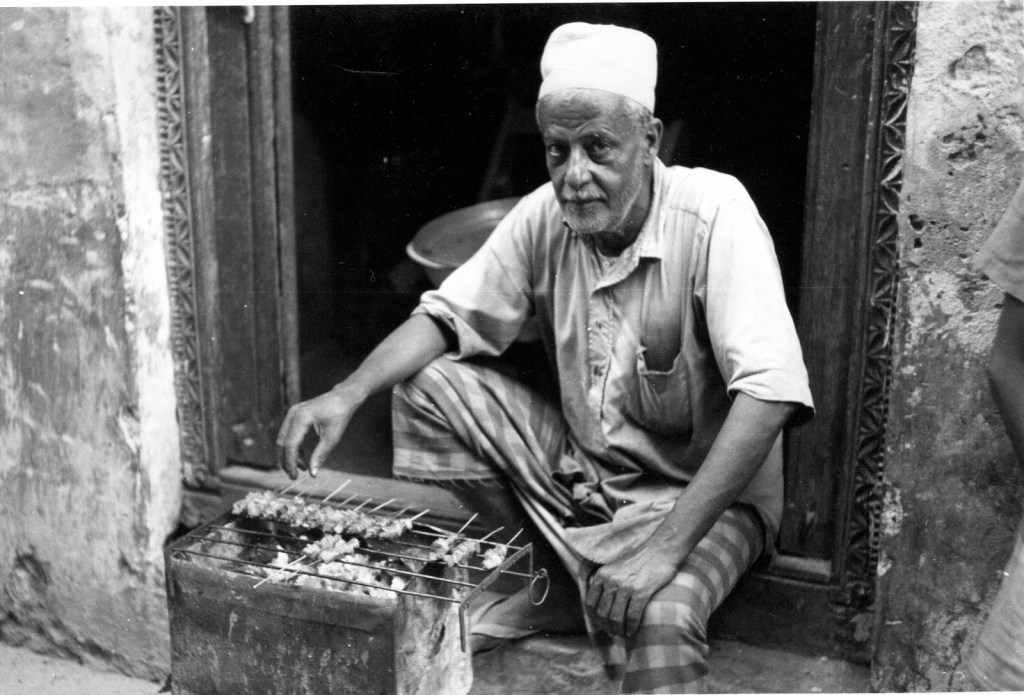

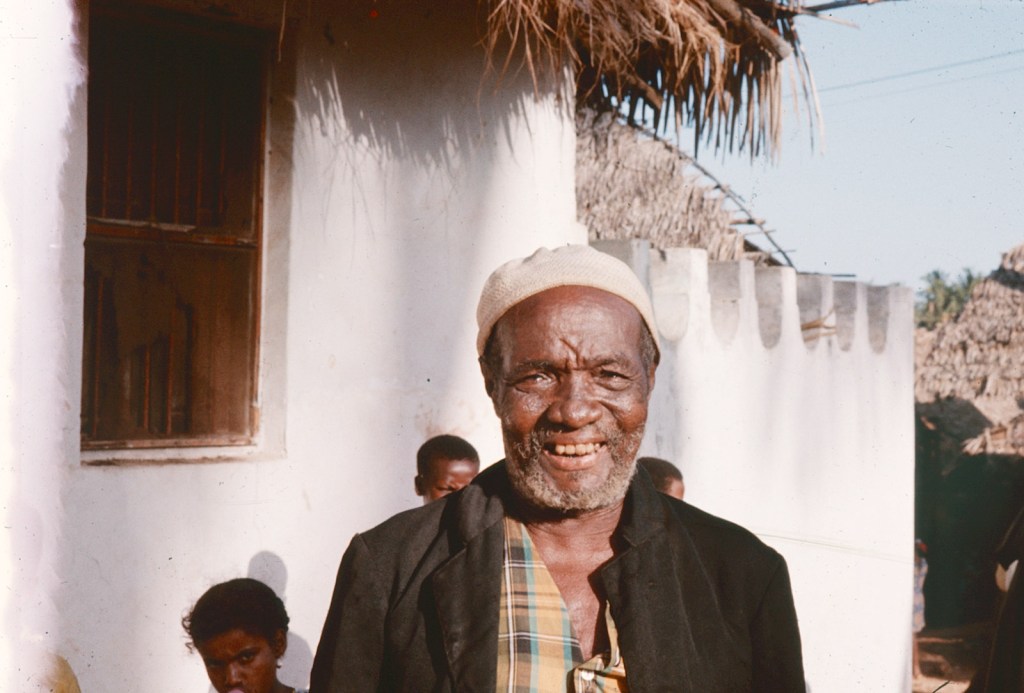

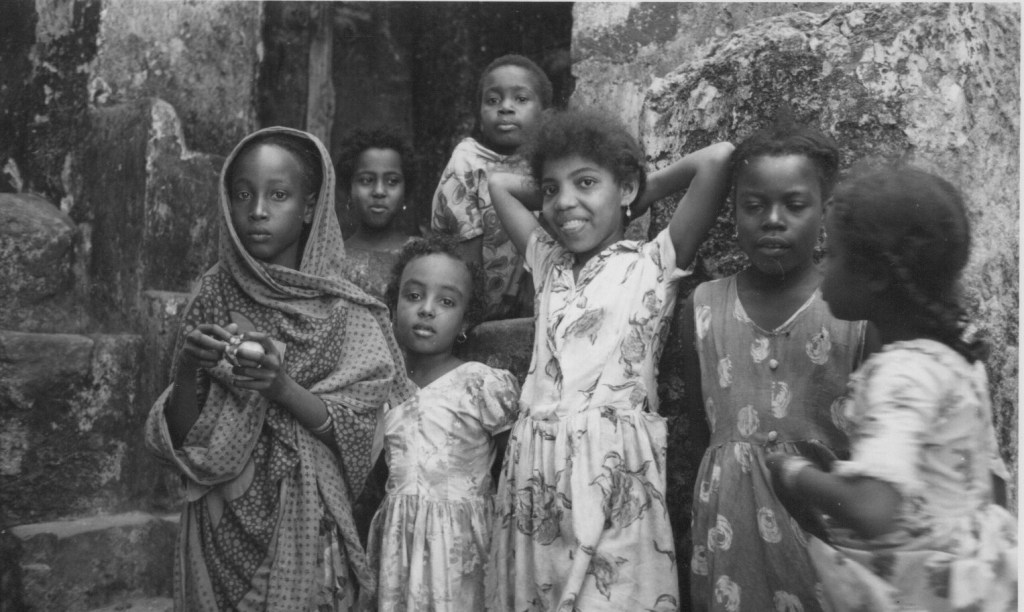

Faces of Lamu

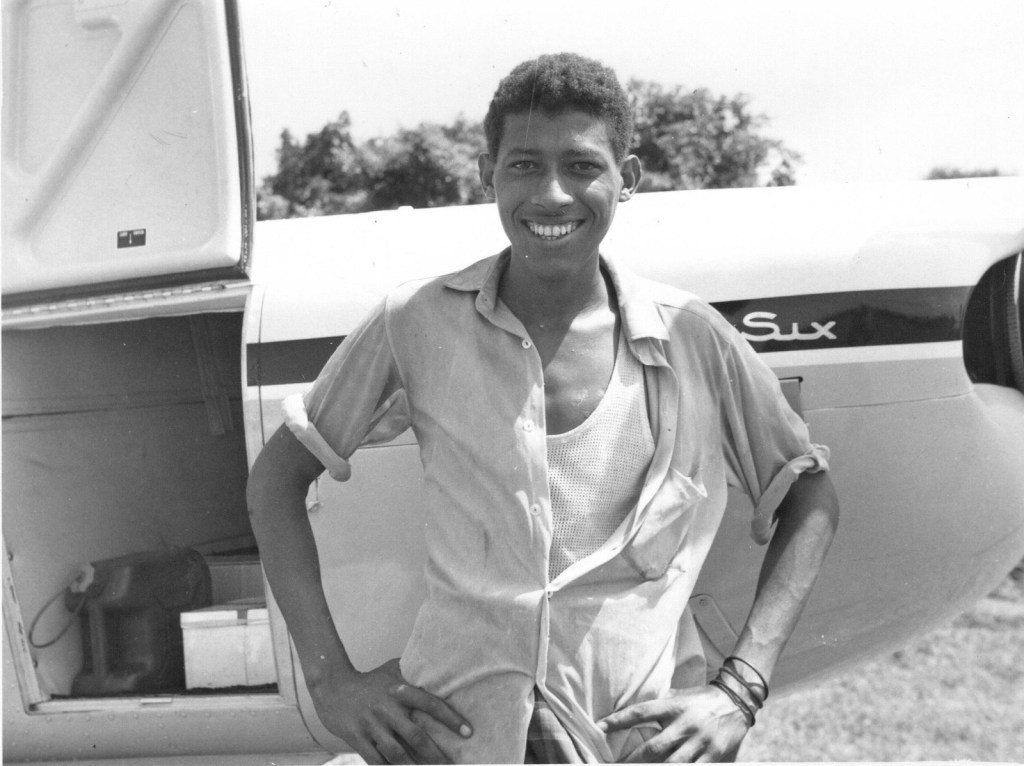

Chui

Another person I bumped into in the main street yesterday was Chui. 20 years ago he was a boatman and his boat, small, green and yellow, was called Kipungani boat, and owned by elderly Indian who shared the earnings with Chui. At that time Chui was about 20, fine physique, strong and muscular, dark curly hair and medium complexion, no breakdown or untoward situation dismayed him, and old Mohamed was his helpmate. Chui was a lad of the town and owned a small house in our building, or part of the house. which bore the name board of Colnel House – whether this meant colonel, canal or colonial, I never found out.

Year after year, time after time Chui’s boat was our main sea transport, generally sailing with a low chug of its old Kelvin engine day and night, in and out of the islands, across the sometimes turbulent water between Pate and Manda.

Well times changed. Chui who was, or became, a homosexual, ran a bigger boat, after the old Indian died, with the help of his little Msaidizi [helper]. The last time he took me out in this was some 10 to 12 years ago when David Gentleman and Barbara Keane were here and we went out beyond Manda Toto and Pate to do goggling in the wonderful sandy dells within the coral reefs out there.

Kipungani boat came ashore, it’s engine taken out and could be seen forelorn and landlocked among the makuti-roofed houses and coconuts to the south of the town near the abattoir – a sinister place not far from the graveyard, where tomorrow’s meals clustered hopelessly in corrals awaiting early morning slaughter.

But Chui didn’t prosper – he took to the bottle and became an alcoholic. Boat went, little boy I suppose went, and he went from bad to worse. Yesterday I met a raggedy wreck of a man, unkempt with stained teeth and rough hair, who greeted me ‘Mama Sheila do you recognise me?’ he asked cheerfully enough. With something of a guess I answered, ‘Of course, you are Chui’, which pleased him, ‘but now you’re an old man’. ‘Well so are you’, he replied glibly and truthfully – and went on his way cheerfully. He was hardly recognisable, but some lucky chance had caused me to get it right and I was glad.

Seems such a long time since that day he got so cross with me at Manda Toto when coming into land, that he more or less told me if I didn’t stop giving advice I could jump in then and there which no doubt was well deserved.

Ali Maulidi

Sheila had two housekeepers for Pwani House, The first was Hamida, a tiny, wizened, toothless Swahili lady with a huge smile who cackled like a witch. She was a real character and bossed Mum around like anything. Eventually she retired to Mombasa where her daughter and granddaughter, the Fatuma of these photos, lived.

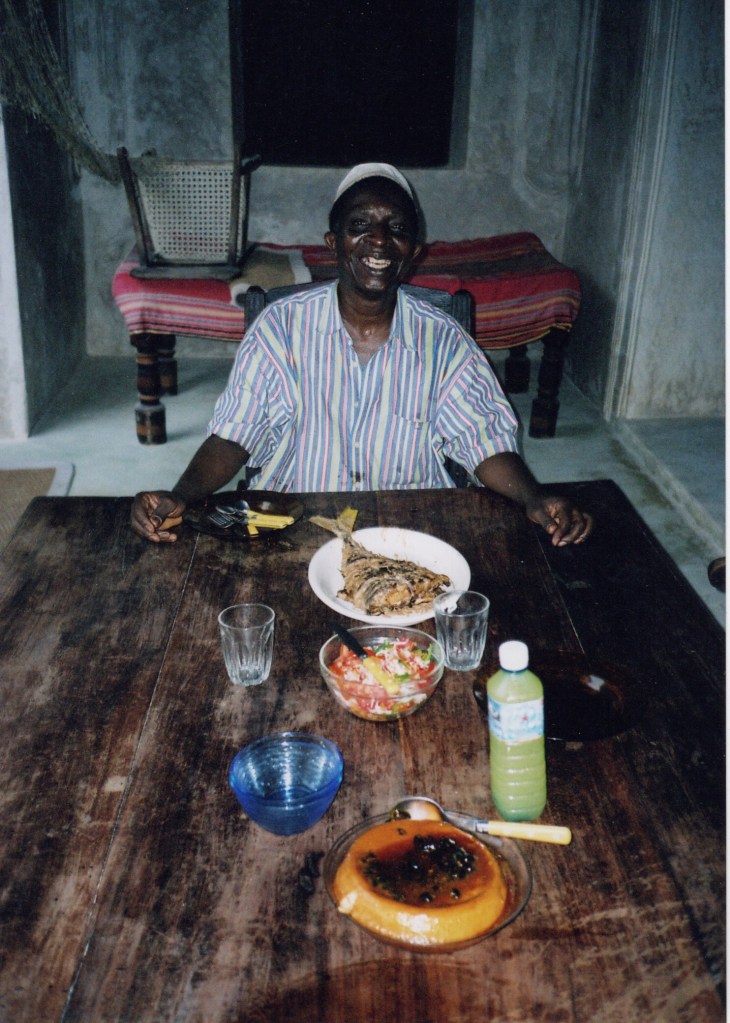

Ali Maulidi took over – a very sweet, quiet and giggly soul – quite the opposite of Hamida. Obviously they knew each other well – everyone is Lamu does. A tailor by trade, he had learned to cook somewhere and was very house-proud. His Swahili cooking was delicious. When Sheila left in 1990 she found him a good job, housekeeping for another expat, who was very kind to him as he grew older and less able. I saw him on both my last visits to Lamu, but I do wonder if he’s still alive. Somehow he survived Covid, and a relative had given him a small house and comes into cook for him. He can hobble about, but not much. He just sits and listens to the radio and people drop by as they do in Lamu. Noone is lonely there. Below are some diary entries about Ali.

Excerpts from Sheila’s diary 1990

The plane landed at Manda airstrip and taxied to the place near the shore where you arrive or board. From the huts where the ongoing passengers were waiting strode a stocky purposeful figure, hatless with shaved head and flapping khanzu. It advanced and folded me in a double bear hug not only to my surprise but to everyone else’s who was watching. It was Kombo! Full of enthusiasm he grabbed my bags, followed by the tall, smiling figure of Ali Maulidi, he in shirt and trousers, who took my Zanzibar basket. Together we chatted excitedly and walked down what used to be a straggling tree-lined path but now open and cleared.

At home Ali had outshone himself, sodas in the fridge (working I’m glad to say) but tea and savouries from Shabar‘s shop were hastily produced when I asked mistakenly for tea, not knowing about the sodas. Then old Mohamed, the pensioned-off boat boy, appeared to find out if it was really true I was here, and a long story about how his house was burnt down in the middle of the night. Hadn’t I heard about it? Hadn’t Kombo told me?

The house looks clean and tidy and orderly – my best cloths and covers had been taken out of their boxes… Later. Ali triumphantly appears with a large roasted fish and a big sponge cake (keki ya mayai) which we split between us, the cake very much appreciated by my different visitors. I like it too. It has cardamom and cloves in it.…

…It is now 12.20 in comes Ali tidily dressed in khanzu, and is off to the Friday mosque for prayers. I’ll be back in quarter an hour, he says which seems to be a short time in which to say the principal prayers of the week…

…Ali tells me the garden outside is his work. Some very flourishing plants are in pots all down the stairs, one with big triangular leaves, there’s a type of ? though no flowers, two kinds of low edging plants and something like a small palm planted in an old kettle, also mint sprouting in a broken enamel basin. He really is a treasure…

…By the back door, rather a nice Kutchi one, we have pawpaws, luxuriant pomegranate, with brilliant flame flowers and green fruit ripening to shiny red, and climbing energetically over the fence between us and Bahamadi’s store, now abandoned and rank with weeds such as the poisonous datura, is a tambuu vine – the heart-shaped leaves shiny and healthy, Ali tells me the tambuu was planted by Hamida, another resourceful being. I think he should sell the leaves when they are ready. People still chew here – the leaves are made up into little parcels, having been spread with a powdered lime mixture, dried tobacco and chopped up betel nut…

…At supper Ali arrives all in white khanzu and trousers, smelling of perfume and announced he was off to a wedding. As I sat at the table a cool wind ran through the house and down came the rain. And not long after that came Ali, somewhat sodden – the wedding having been rained off. He was feeling chatty so he sat down and and an odd conversation followed, partly in English, partly Swahili, ranging from personal likes and dislikes to why the Queen wouldn’t come to my wedding if I had one, which was a great surprise to him. He and, I dare say, others can’t understand that one isn’t necessarily rich if one comes out here now and again, and has a fridge in a cold place like England. Of course we are all wealthy compared to them but it is hard to get them to see that the cost of life in England is far greater than here even though some things may be cheaper.…

…I think Ali is getting rather tired of having me around – his cooking has become somewhat ordinary and he forgets small errands – perhaps this is because it is Friday. He told me he has been to the mosque five times today (I bet he didn’t go at 4:30 if so I would’ve heard him) and has been dousing himself with strong sickly perfume since midday. My fridge is the supplier of ice to all his relatives and friends – and he has as many as Rabbit [reference to Beatrix Potter]. I’ve had to instruct him about defrosting, not using a knife in the freezer compartment, not opening the door too frequently. Tomorrow we must defrost.

Last days 22nd and 23rd of December

Ali meanwhile has turned into a typical Lamu harpy, insinuating he would like this and that, some glasses, some bedlinen. ‘I haven’t got a towel’, he remarked; most unlikely as he seems to possess just about everything else, and even a glass-fronted display cabinet in which he thought the pretty remnants of some small glass oil lamps would look nice. I was really too uncertain of my myself to do more than remonstrate but I did make heaps of pillows and blankets and so on for Mohamed, for Omari Barroso and Haji Saidi [see his picture with me making halwa at the top of the page]though the last two never turned up. I hope they got their gifts.

Barosso’s carved fish for Vicky remained a happy thought and Haji, who usually produces something like cake and halwa just as one steps onto the boat, I suppose got into a Lamu muddle or at least would say they did. Sad not to see either of them but I was thankful not to have to find room for anything they might have brought me.…

My last hours in Lamu town were spent struggling with Kombo and the bank manager… Hardly any time to say goodbye… I rushed out to catch the boat which was just about to push off. And Ali, smiling and competent came over with me… [and this goes back to] How can I leave this place I wrote on arrival – easily and thankfully I can right now.

PS

Sheila did come back over the years with various friends, staying at Pwani House but as a guest. She found it much changed as her old friends died off, and good manners with them.