Manda

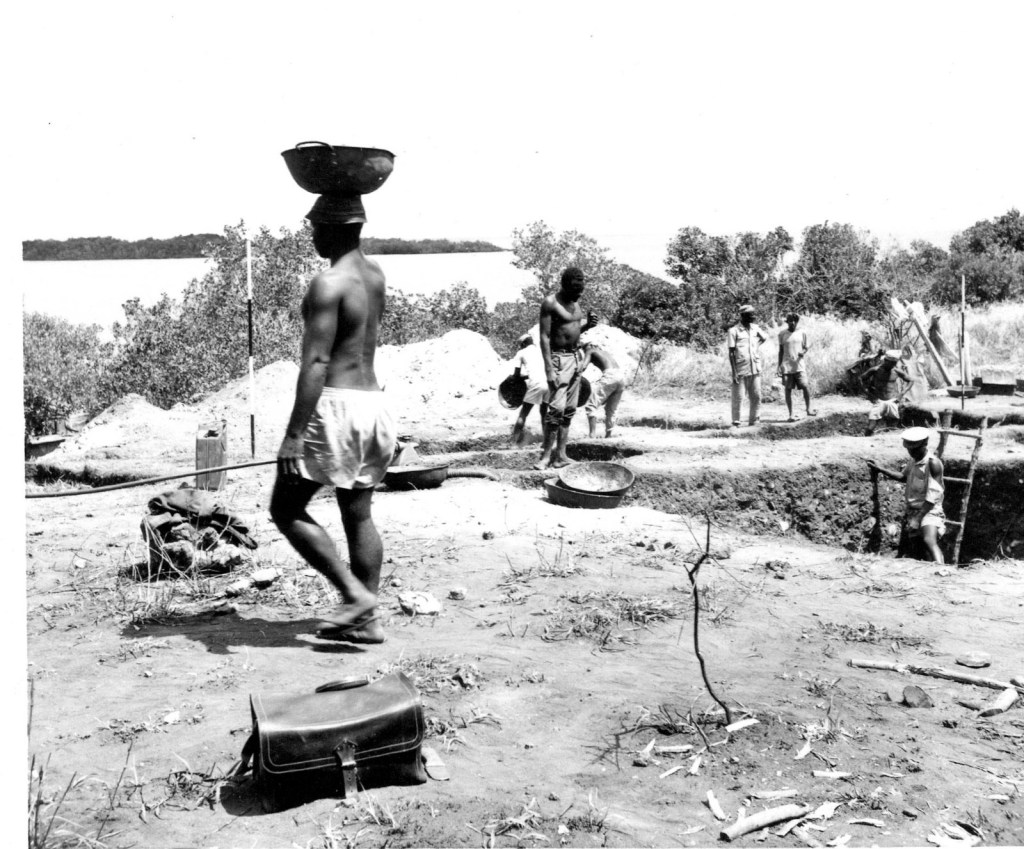

The Manda ruins at Takwa, opposite Shela in Lamu, and in Manda town, itself were first explored by Neville Chittick in 1965, assisted by my Mum Sheila. They camped on Manda Toto, separated from the mainland by the Uganda channel.

The dig revealed a prosperity unrivalled in Eastern Africa for the period, and included Chinese porcelain dating from the early ninth century, Islamic pottery and glass, and local pottery dated by associated imports . There were seven periods of Manda’s prosperity from the mid-9th up until the late 17th century.

The unique brickwork discovered on the site are likely to have been bought in from Sohar in modern day Oman, again underscoring the importance of the Indian Ocean dhow trade. Exports from Manda were probably predominantly ivory and mangrove poles.

The Manda settlements were probably abandoned in the 19th century due to the lack of water. It is now a rich person‘s playground with large houses, water imported from Lamu, an airstrip with a few small holdings dotted here and there.*

In 1965/6 my mother had just left my father to spend more time with Neville and I think she was at her happiest. This is why I buried her ashes on Manda Toto, later to be joined by Louise and my father. A peaceful and remote place to rest.

Siyu 1990

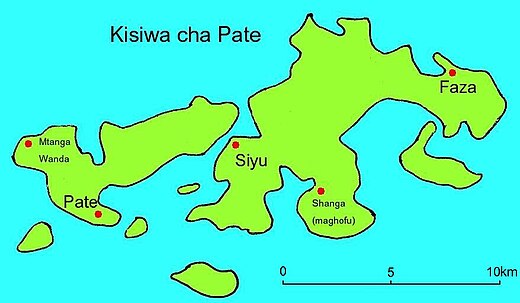

Siyu’s age is not known as no major excavations have been done in Siyu – aside from Neville’s site visits (with Sheila as evidenced by the old photos and her diary below) in 1965/6 – but it might date from the 13th century. Gaspar de Santo Bernadino visited the town in 1606, and stated that it was the largest town on the island.

Siyu’s main claim to historical fame is that it withstood the Sultans of Zanzibar in several battles. In 1843 the Sheikh of Siyu, and the new Sheikh of Pate, repudiated the sovereignty of Seyyid Said, Sultan of Oman and Zanzibar. In response, Seyyid Said assembled an army consisting of 2000 people from Muscat, Baluchistan and Lamu. It landed at Faza in early January 1844. On 6 January the army moved towards Siyu, but were ambushed and forced back to Faza. After three weeks without a victory it sailed off.

When Siyu finally succumbed to Zanzibar’s dominance, under Sultan Majid in 1863, it was one of the last towns on the whole of the Swahili Coast to do so. *

In December 1990, Sheila went to Siyu on Pate island, to do some research on the local handicrafts. Here are some excerpts from her diaries. Even then it was pretty primitive!

Her host was a Siyu man, Bakari, who lived in Lamu and was returning to the village to see his family. The boat journey would have lasted 3-4 hours, chugging between the channel separating the island from Manda, and then the open sea of Manda Bay, skirting the reefs on towards Pate.

We headed first south-west then turned into the Mkanda channel north between Manda Island and the mainland through a deep patch of water open to the sea and then alongside the west of Pate island. We passed several dhows, some out fishing and on business, others with tourists.

The first stop was Mtangawanda [Pate Town ‘stop’] where 20 or more souls disembarked at the crumbing jetty and then on again, hugging the shore of the island until the opening for Siyu was reached. We pulled in at another small jetty, in the middle of nowhere among the mangroves and most of the passengers climbed out and the boat chugged away to Faza.

About seven women in buibuis [black cover-all] and two or three children were then taken on to Siyu in a kidau [small sailing boat], the causeway from the jetty being said to be broken and the way muddy. It was a 25-minute walk anyway and though I was willing to go, no one offered to help me with my bag so it was decided the boat was best for me. I sat astern, the old man poling along behind me, shouting away in unintelligible Swahili – in the Siyu dialect – as we slipped along, I bailing out water with a yellow plastic scoop.

After 25 to 30 minutes, Siyu appeared round the bend in the creek and we clambered out into the shallow water and on a muddy shore. To our right, the west, are the towers of Siyu Fort, which look imposing, though aren’t very old – about 150 years, I seem to remember – and beyond the shore is Siyu village, coconuts, palm-roofed houses the walls, and crumbling ruins here and there. Siyu the city of craftsman, famous for hundreds of years.

Bakari had arrived and escorted me to the house, a throng of inquisitive small children fore and aft. The path twisted inland and in and out of closely-built huts each with a high step up to the front door and many with solid ceilings over topped by high-pitched makuti roofs.

At last we reached the house, his wife was sitting on the front steps, Binti Ali and her father, Ali Mohammed…she didn’t seem very pleased to see us, I think because the letter telling her she had a guest hadn’t arrived. Anyway after some altercations I was shown to my room -with a huge Indian bed, Moslem type, inlaid with tiles of glass painted with flowers and an ornate canopy for a net…the bathroom was shown to me and proved to be clean, having a large water birika [tank] and a choo [loo]behind a walled division. This was a relief, remembering the obscene toilets of Faza.

The next morning Bakari departed on a bicycle to see his sister about a circumcision in Faza, having ‘enrolled the headmaster of the primary school to take me round, Omari who I discovered later is the husband of Bakari’s adopted daughter. He turned up at about 8, a pleasant young man in is mid twenties, the with a small moustache and off we set.’

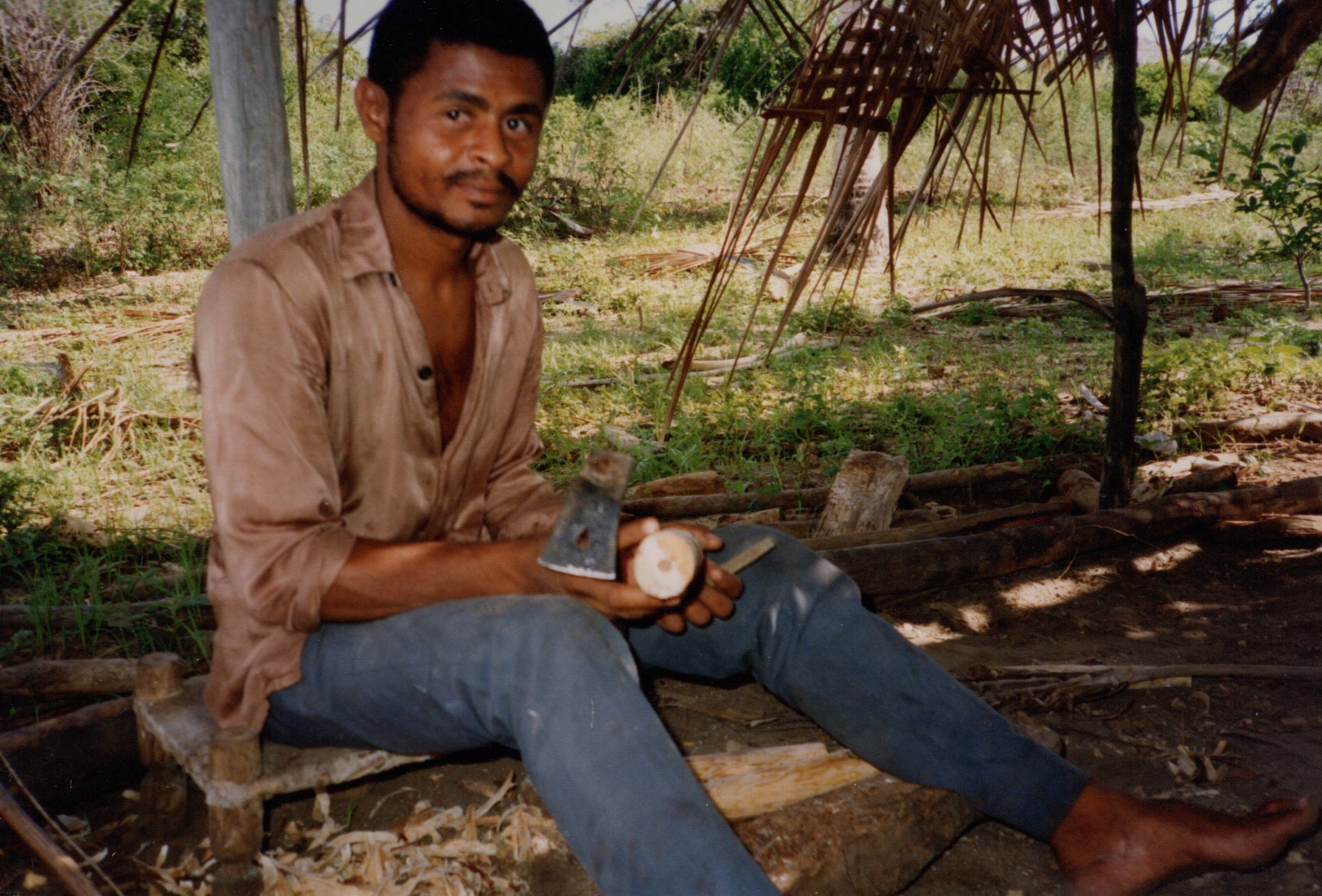

We wandered in-land between the makuti roofs to an area of ruins passing a very old mosque which I remembered from my previous visit of over 20 years ago. Then it was inpenetrable but now I can just about get in. The mihrab is fine and lobed with two nicely-carved bosses on either side of the top, and there’s a small minaret, not of the accepted sort, but with steps up to the roof. The tops are mounted by a crown-like cover, rather elegant. We strolled on through twisting paths, past the Friday mosque with a similar minaret and in better order, as it’s in use, and so to the little shelter where the maker of stools does his work.

There was a young man working away on a set of legs and he was happy to tell me all I want to know. It was almost the same as they do in Pakistan and India. Then the old fundi appeared and we had a long talk about traditions and beliefs, who made what in the past. It seems to run in families here too. I took lots of notes and and photographs.

Here they are turning the legs of a Siyu stool, using a traditional lathe ( I have two at home)

After we left we went to visit an old domed tomb. In fact there were two which had originally been decorated with lines and rose of blue white Chinese bowls. When I’ve seen it over 20 years ago, numbers of them remained some even undamaged but now not one. And the silly thing is it’s almost impossible to remove the plates whole. It did seem sad.

Omari then came just after 4pm and we went off to visit the sandal makers, who work in an open makuti-roofed banda. There were three of them including a young boy. There are two kinds of sandals, the best having two rows of stitching.

After the leather workers a tour of the town with a welcome at every door. We stopped to collect Omari‘s goat from its compound.

We came back to Bakari‘s where we found that gentleman stretched out on the kitanda [sisal-roped bed] in the entrance hall, groaning at how tired was after his trip to Faza [on a bicycle!] and all the mosquitoes which are very bad.

It transpired that tomorrow Omari will accompany me [to Lamu on her departure on the next day]; we should leave around 8:30 and and hang about for the boat at the channel entrance for some hours in the hot sun. This won’t be very pleasant.

It turned out to be another uncomfortable night, hot and buzzing with mosquitoes, but she set off the next morning for the boat back to Lamu.

Well in retrospect it was a truly terrible day. Seen off by Bakari and in the company of Omari we set off just before 9 am, walking the 25 minutes to the jetty, first through thick bush, next plantations of coconuts with the odd date and tamerind here and there and, finally, over salty muddy coral and mangrove flats, covered by the sea when the tide is high. Children and grandmothers and one or two other people were waiting in the kidau and we pushed off down the channel to the sea.

Once arrived we made for a sandbank, the tide going down all the time, and hung about whilst the young cavorted about in the water and on the sand. Soon, we were all summoned into the boat and we pulled away into slightly deeper water and we drifted around for two hours, awaiting the arrival of the boat from Faza. It was very hot. I kept thinking ‘in x this will be over. It will be better when the boat arrives’ …

Fishing while waiting for the boat to arrive!

…and eventually a speck on the horizon grew bigger and bigger and she pulled up some distance away. We poled over, came alongside and clambered in. Luckily, it wasn’t very full and Omari and I found spaces in the gunwales, but unfortunately on the sunny side. I draped myself in two khangas and prepared to sit it out, but it was horribly uncomfortable and hard, and oh so hot. By the time we returned to Lamu we had been on the go for almost eight hours.

Ali was at the steps to meet me. It was good to see his wide smile and friendly welcome and together we walked a few yards home and ice cold soda at once.

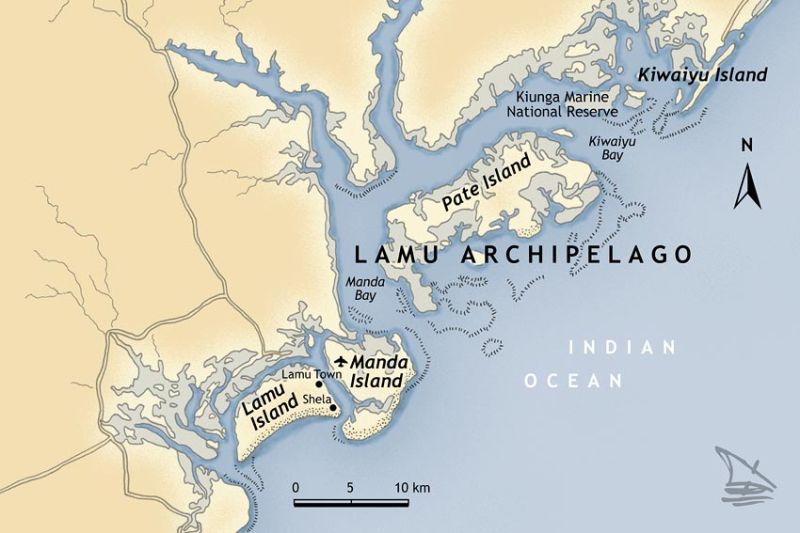

Kiwayu

Kiwayu is an island in the northern part of the Lamu archipelago (see map at top of page). It is not known for its ancient sites, but is famous for its beaches, snorkelling, sailing and turtle-nesting.

Neville and Sheila travelled to Kiwayu in 1966, probably as part of the survey for the Manda and Pate digs. All that I can find are a few photos of Ndau, the main town.

Shanga

Shanga is an important archaeological site, situated on the South-East coast of the island of Pate. It was excavated during an eight-year period, starting in 1980. The earliest settlement was dated to the 8th century, and the conclusion drawn from archaeological evidence (locally minted coins, burials) indicates that a small number of local inhabitants were Muslim, probably from the late 8th century onwards, and at least from the early ninth.

Shanga was abandoned between 1400–1425; the event was recorded in both the History of Pate and in oral tradition. The Washanga (the people of Shanga) consist of a clan who still live in the nearby Swahili town of Siyu (see above)*

Sheila and Neville visited Shanga as part of the Pate/Manda site visits in 1966.

Matondoni, Lamu island

Famous for boat making and its prawns!

*Thanks to Wikipedia for the historical background – I am a donor so unashamed in using its content!