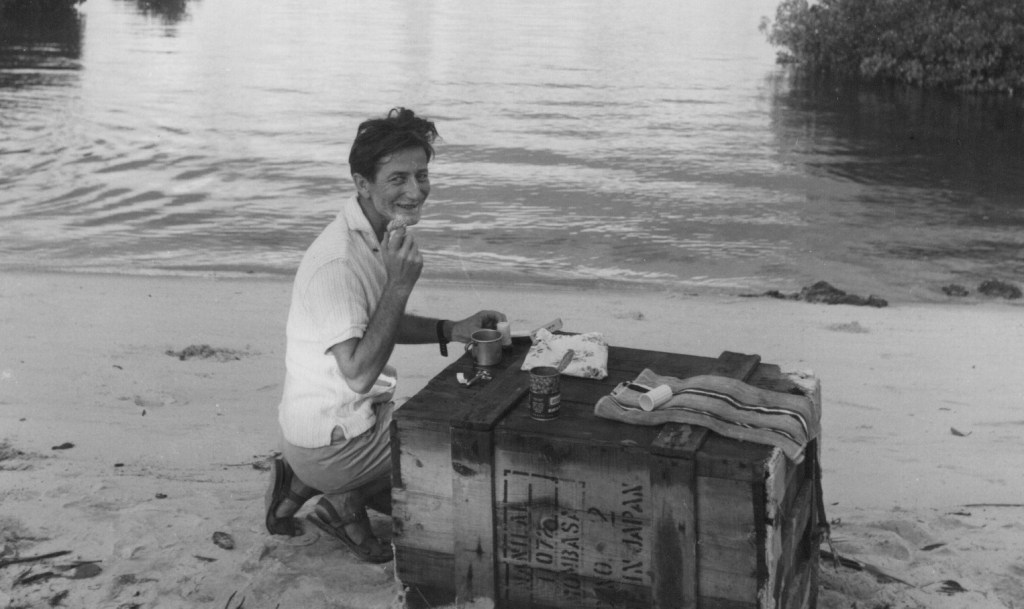

The first and only reference I can find in Mum’s letters to Pate was in October 1966. She describes camping on the beach but they were bitten to death by sandflies and mosquitos and had to move to a rooftop. This was after she had been camping on Manda Toto, when she was helping Neville excavate the ruins in Manda (see Manda pages) before coming to Pate.

The photos that follow are all from that period; and then there is along description of a wedding she attended but with few photos as she was having camera trouble…

Excavations at Shanga

Neville Chittick led an excavation between 1965/6 to look at the Shanga ruins near Pate town. They cleared the Western Mosque and the wells near the Friday Mosque. Evidence from pottery, beads, glass and coins suggested that this was a thriving Muslim settlement in the 8th century, with trading links to Asia.

According to the Pate Chronicles, the history of Shanga began in 600 AD, with the arrival of Sulaiman ibn Sulaiman ibn Muzaffar al-Nabhan, the ruler of Kilwa for 40 years and founder of the Kilwa Sultan dynasty. Sulaiman married the daughter of the king of Pate, thus giving him authority to rule over part of the island. Shanga was an independent town at the time of this event, so it did not fall under Sulaiman’s jurisdiction. It was Sulaiman’s descendants, however, that were eventually responsible for conquering Shanga later on.

Sheila’s old friend Dr James Kirkman was the first archaeologist to excavate Pate in the 1950s. He and his wife Dorothy had retired to Cambridge when I was a student and I used to have tea with them every now and then. They came to my graduation. He wore a bow tie every day, had a stammer but was utterly charming and old-school. His final job had been as Curator of Fort Jesus in Mombasa.

Later excavations reveal that Pate remained a thriving port until the 15th century when it suddenly collapsed, and the town of Siyu took over – also on Pate. It was probably due to a failing water supply rather than anything more sinister.

The site itself extended to 15 hectares/37 acres and had the largest number of tombs discovered on the East African coast – 500 discovered, and more in the sand dune. There we are also a minimum of 185 stone houses in the town with the rubble of at least 35 other houses nearby. The existence of the Friday Mosque, going back to the 11th century, shows there was a viable Islamic settlement in Shanga. Indeed, it was a large town.

I fist visited Pate with Mum in 1968/9. We stayed overnight in one of the ancient houses and it was pretty horrible. Very hot – especially the walk from Mtangawanda to Pate town – and swarms of mosquitoes. No beds to sleep on, just mats on the roof. Obviously no electricity or running water, and the long-drop loos were pretty filthy. It took me a long time to get over it! Here a photo of me on the boat with a friend of Mum’s.

A wedding!

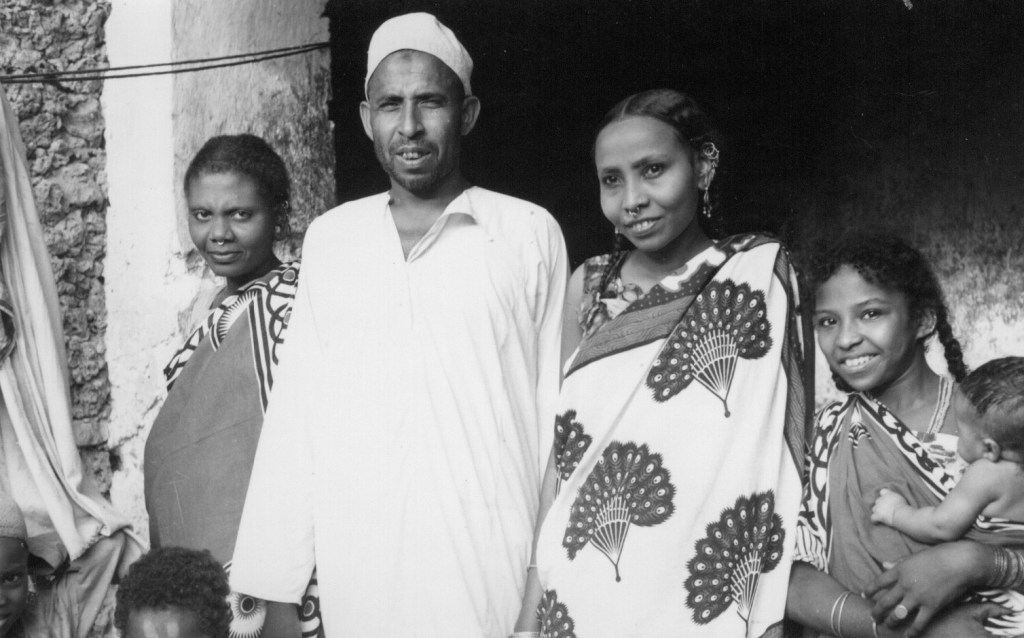

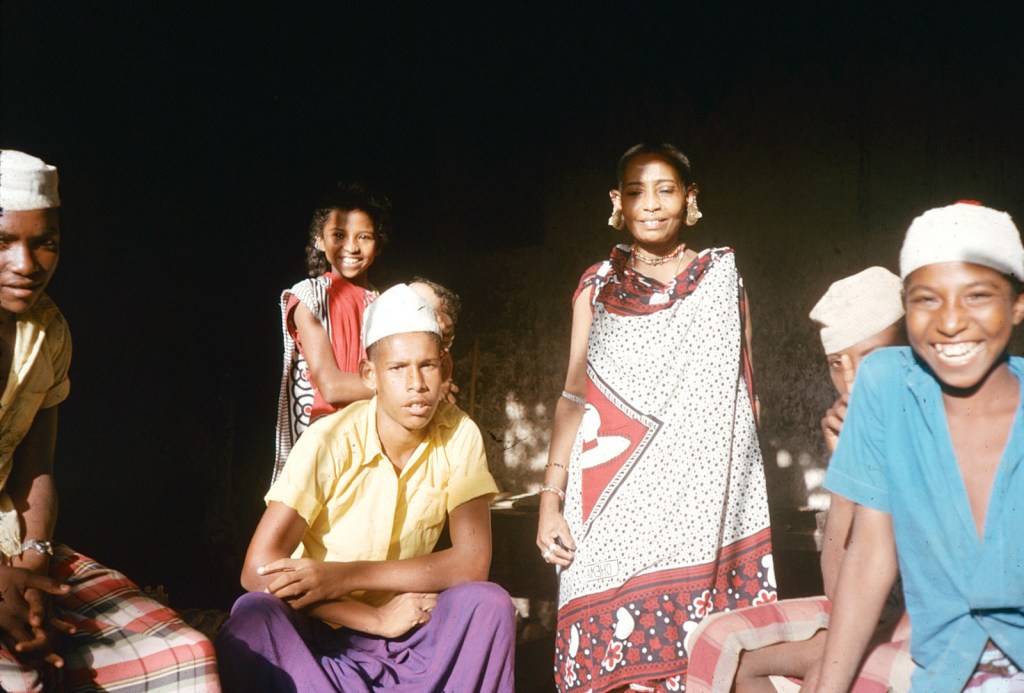

At about 2 pm female relatives the bridegroom go to the bride’s house, where they are welcomed by the family, given a drink of water and offered popcorn and, separately, coffee beans roasted with a little maize, sugar and coconut oil. The family women are all dressed in bright pairs of khangas and fine golden jewellery. Small rings (vipule) all down the outer edges of the ear, followed by mbambao and small crescents, the lobes with finally worked majasi or circular boxes about 1/2 inch thick with applied strips, discs and diamond shapes.

We are then taken to the house next door to have a look at the bride. Both houses are clean and tidy and each has fine beds in the outer veranda – the first house having a hand-painted Hindi bed, complete with canopy poles and fine mkeka [mat] laid over the stringing. In the second house, the beds are more modern, of Indian pattern with centrally supported net frames in the inner room, which has a well preserved plasterwork – vidaka – in the wall .facing the door.

The bride sits on a bed behind a screen of curtains. We draw it back to look at her – she is not young, but looks pleasant and shy with downcast eyes, a dark khanga around her head. The husband, a relative of Nana [her agent’s wife, from Faza in Pate], is over 40 and a bachelor so all seems very suitable.

We then return to the first family house where a big bowl of clean tea cups was brought in; these are laid out on sinias [copper trays] and everyone is handed a cup. Trays of doughnut-like mandazi and sugar dough triangles are handed out – as the first food of the day, they are most welcome. We sit on mats under an awning in the courtyard.

About 4:30 all the women set out again and welcome the guests from Faza. We walked out of the town towards Mtangawanda along the salt flats, waiting under some coconut trees for all the visitors to arrive. There was much delay because two of Nana‘s aunts had taken the wrong road and had gone off in the direction of Siyu instead of Pate. We hang around for some time, small boys tapping out the drums and women shaking tambourines. A man with a blowing instrument, a kind of reed trumpet, called msomari, practised his tunes. When it was decided to wait no longer we all processed off to Pate singing, clapping, rattling tambourines and banging the drum to the accompaniment of the msomari. I was told the songs were special for weddings and no more than that, so I suppose somewhat salacious.

Every now and then we stopped for a special song to be sung and then again then on again through the town to the house of Mwana Esta Aboud, our hostess and relative of the groom. By this time there were so many visitors that the place was rammed so I left with my little bag of popoo nuts which I had bought for Saidi Haji, Tabir and other old friends. The nuts were divided up by Saidi, and I then went off to Tabir’s.

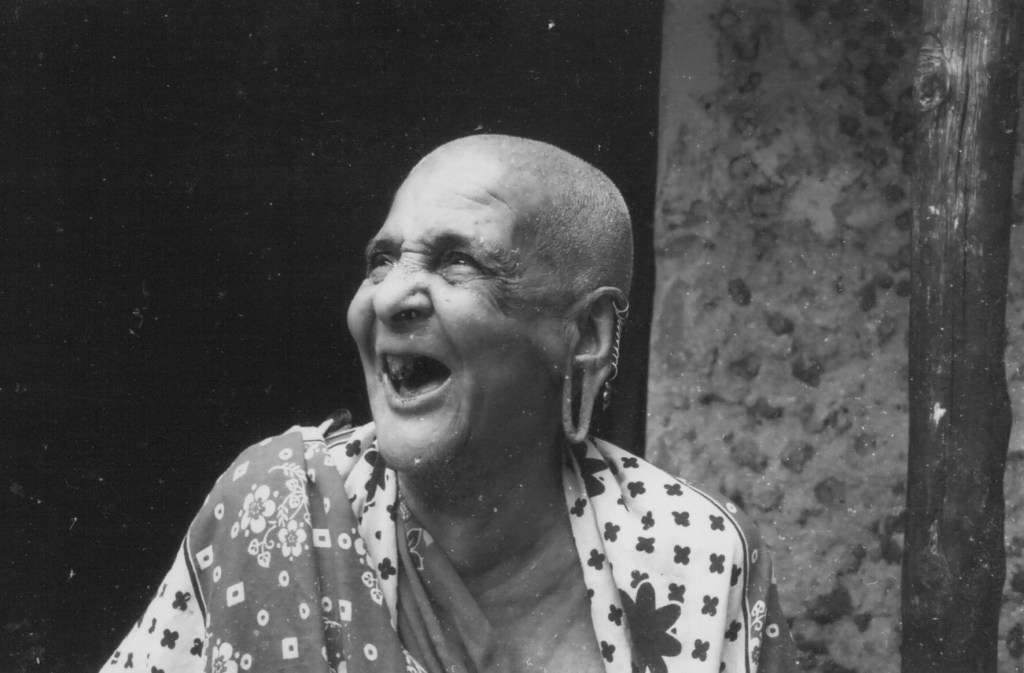

She was sitting plaiting a section of a mat in her dark somewhat primitive and grubby house. All chairs and beds lined the walls. The younger relative was grating a coconut whilst another dashed out to buy me a Pepsi, the money having to be undone from knot in Tabir’s khanga. She is over 90 and doing very well, she says she’s poor but nonetheless insisted to rush out and buy me two mangoes and another relative brewed up hot, sweet milkless tea which was very welcome. After consuming half of each I gave over the rest of those standing around. Saidi had some of each drinking his tea from the saucer as is customary.

We left them to watch some ngomas – drumming and singing near Esta‘s house – after which I went for a walk round the houses. Many greeted me by name, old people remembering, young people catching on to something novel and shouting my name continuously. Children here have always been rowdy.

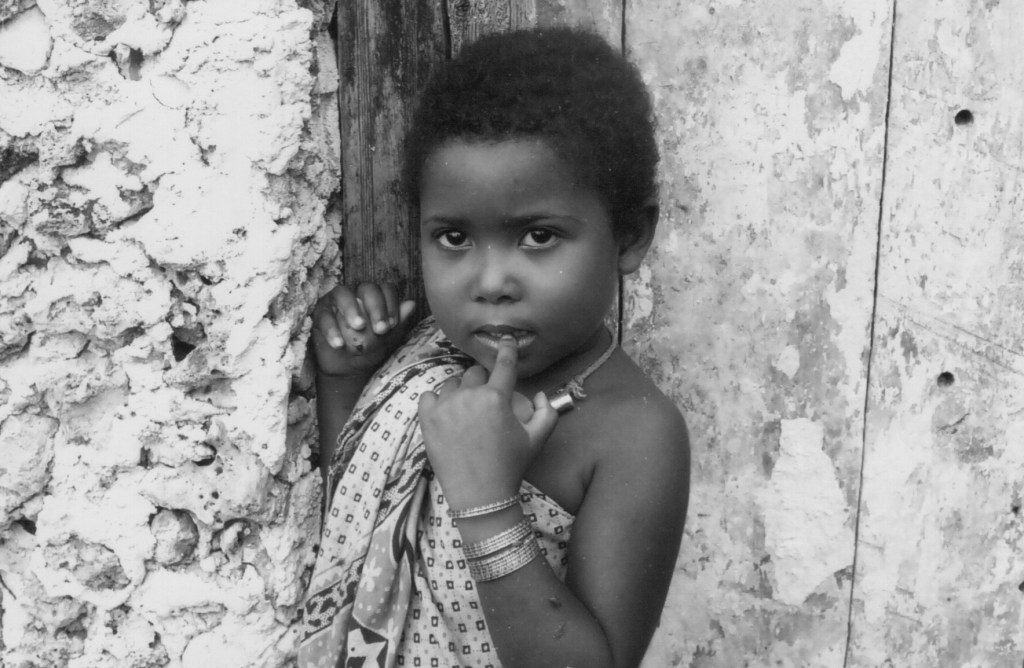

Near the seashore I came upon Bakari Khalifa, a relative of Mwana Atika. He took me to his house. He has an upper room where he says I can stay should I come again. He bought his daughter Atika to show me and I took the photograph [below] sitting on the roof in the half light with flash as it was around 7 pm. I thought I better get home in order to get ready for the next marriage event which is to escort the bride groom to the Bride.

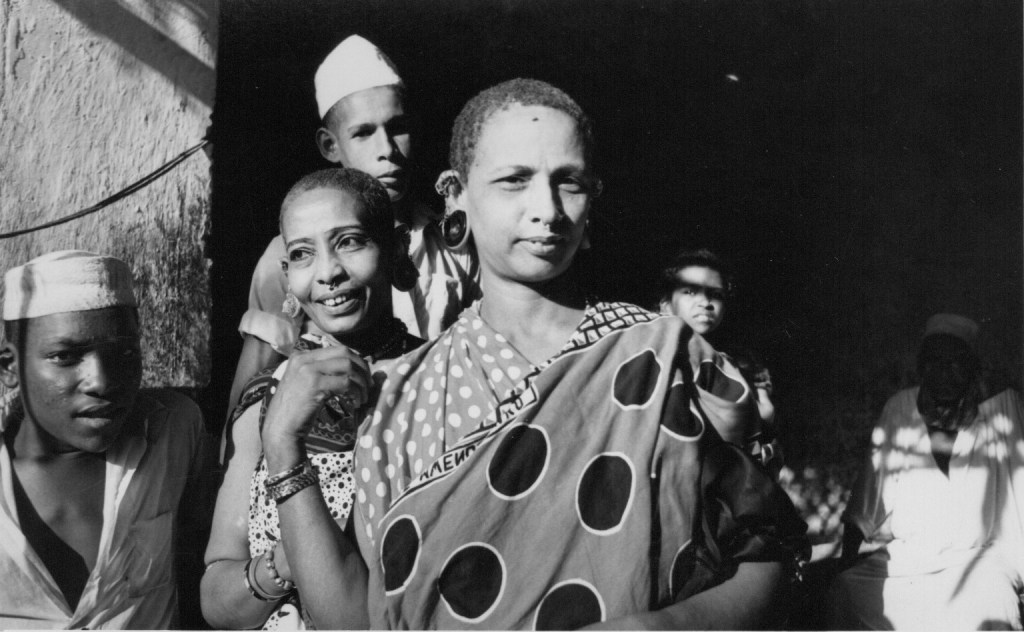

I found that I had been moved out of Esta‘s house to a neighbours where Nana and the rest of the Faza lot were getting dressed. Yet another a lot of glamorous dresses had been fished out of their luggage, even huge Khadija was robed in a voluminous brightly flower dress with khangas. Nana was in a basically brown creation with a gathered top and overskirts of a pretty tawny flowered nylon georgette, and was busy making up her face and eyes. She is clearly the success of the family, emancipated and smart and she knows it – bidding everyone including me to hold things for her, or put away something else, find whatever she has lost. They had all had yet another bath and were somewhat surprised when I said I didn’t want one. I’d come to the end of my clothes and though I wanted to wash and have and have a cool drink, or even a cup of tea, it all seemed pointless. The children, all boys, were being skinned of the last lot of finery and clad in the next lot – mostly all made of women of woven nylon of a terylene type – no wonder the baby yelled.

Then it was time to go. We sat outside in the street on small beds until the bride procession came out of Esta‘s house. Everyone was dressed in smart white khanzus and the groom himself, who turned out to be the strong quiet middle-aged man who sells old things who I’ve known for years, had a dark blue bandanna wound around his cap and a blue sash [?] over his khanzu. He wore dark glasses which I understood is to help his help him overcome his shyness. Someone held a large black umbrella over his head.

The women snaked down and back lane in order to be in position to face the procession, which filled the narrow street not only with people but with beaten drums, young men raising mkwaju sticks in time with this their songs and, walking backwards facing the groom, a man with a karabai on his head, between them Saidi Haji singing with all his strength – this serious faced man even tragic-looking is a famous singer and, clearly, had the main role this evening.

I fell in with Bakari Khalifa who urged me to take some photographs. I was cross to have missed the groom. Nana naturally got the best viewing point and to tell the truth I would have thought of photographing had not someone else taken one. After this I took something on chance as it was so dark and it was impossible to see how the camera was set. [There are no photographs!]

The procession wound through the little lanes not more than 4.5 foot wide passing Mwana Atika’s house where we had stayed and then turning left under the archway next to one of Bakari‘s houses up a slight incline and then onto the corner where the bride’s house was and she no doubt waiting fearfully as the meeting grew nearer and nearer.

The men having reached their goal, it remained for the women to follow on. They were quite away behind, singing, singing, ululating now and then and beating drum and tambourine, the msomari accompanying them. They stopped halfway up from the archway and continued singing until the men abruptly returned saying, ‘It’s all over’ and turning back in the centre of the town.

Now it was the turn of the women to visit the house and this they did crowding into the courtyard and chanting in unison. After a while they moved over to the house next door, where we had tea and the kashafa [?] and for a short while pairs of young women bound khangas round their bottoms and wriggled them in time with the music, shuffling from foot to foot. But it didn’t last long and soon the women broke up, clusters of them chatting together whilst others drifted off home, children dangling on their hands or smaller ones carried in arms.

We went to sleep in this house next to the brides and so I led Khadijah back to where our bags had been left, meeting Nana on the way and together we returned to the courtyard full of beds overlaid with mats, many of them already occupied. Nana and I found one in the first inside room opposite the doorway – very hard it was but had a mattress, only one pillow though. As these were in short supply I rolled up my bed cover, judging there were few mosquitoes and after spraying the exposed parts of me and, laying my long gown over my legs, went off to sleep.

During the night children stirred and asked to be taken to the choo [loo]. At around 5 am mothers awoke, roused their babies and with soft words of encouragement induced them to kojoa [wash] – the older ones imitating them and presumably complying as soon you could hear the running of the kopo [water tank] on stone and the splash of water as they were cleansed.

By 6.10 I washed after fashion, dressed and packed up – no boy with the donkey to take my bag had turned up so Nana who, rather surprisingly, had awoken and was showing concern took me over to Esta‘s house to see what was happening. No one up there so we sat outside the neighbour’s house to see if he turned up. The neighbour turned out to be an agricultural advisor from Thika stationed at Pate and we talked about education and he told me out of 300 children only 30 to go to school. Pate needed educated people to broaden its view and replace people like himself from up-country. We also discussed wango an ingredient of halwa, which is a tuberous-rooted wild plant and he said he would bring a plant to allow me to show me if I stayed on long enough.

Saidi Haji now appeared and on hearing my plight said Mahmoudi would take my bag – it was a kikapu but too heavy for me to carry. This young man duly turned up – he must be 16 or 17 now and off we set together my kikapu on his head. His mother came running after us with a kuku [chicken] as a parting present, poor long-legged white creature, I would willingly have set it free and not subjected to a long frightening safari.

And so we walked to Mtangawanda, which took an hour, only to find no boat. Quite a number of other people had come along too. It seems that a boat from Faza was likely to come but at 9:30, now, no sign of it.

No boat came and a small crowd sat forlornly under a thorn-bush, wondering what to do. A plump Pate man in trousers and bush jacket, embroidered cap and a beard suggested we might hire a dhow between us. He went off to enquire. It was clear he hadn’t succeeded in his bargaining for he hung about on the jetty and when asked. on sauntering back, said 300 shillings was the price and that’s too much. I agreed. He said well he will wait till the next day and what did it matter about food? I didn’t agree with him as, though not hungry right now, was very thirsty and, with only two mangoes from Mwana Tabir, didn’t think it would be much help as they’d have to be shared. We waited on Mtangawanda, place of black sand, really describes it. I wondered what minerals it contained?

At about 11 the wedding guests arrived to board the beached Jamhuri, waiting for the tide to return them to Faza. I didn’t feel enthusiastic about them as they had not hired the boat and it could’ve taken us to Lamu.

Small girls teased their parents, saying the boat was coming. No one believed them but someone thought they heard an engine. I rose and walked down the shore and to my great surprise a boat was approaching – no one then believed me until I said ‘Haki ya Mungu’ [God’s justice] and they went to see for themselves.

It was indeed a small boat but had enough room for all of us. I climbed over the side with difficulty, no ladder in such a small class craft and the canvas tarpaulin for the shade was very ragged. Still we set at 11:30 hearts high. Almost at once the water cooling pipe fell off its connection, resulting in slowing down and all hands to binding it on. This done, speed was put on and off we went again. Next the tarpaulin was rolled up, I wondered why, but discovered the reason.

Once past the end of Pate island, the seas rolled unabated, first causing the boat to roll with them, and soon to ship water on the weather side, on which I was sitting. It was fun at first to have waves spraying on one’s face. I moved my watch to the right arm and sat facing the sea and hoping not to get too soaked. In no time at all, I was drenched to the skin and unable to move so not to upset the balance of the boat.

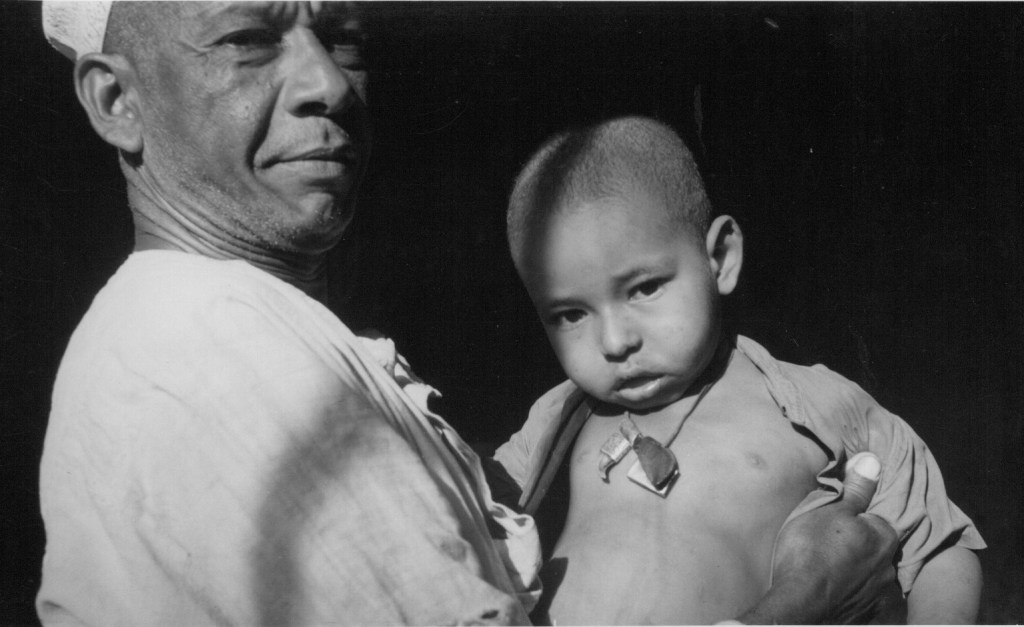

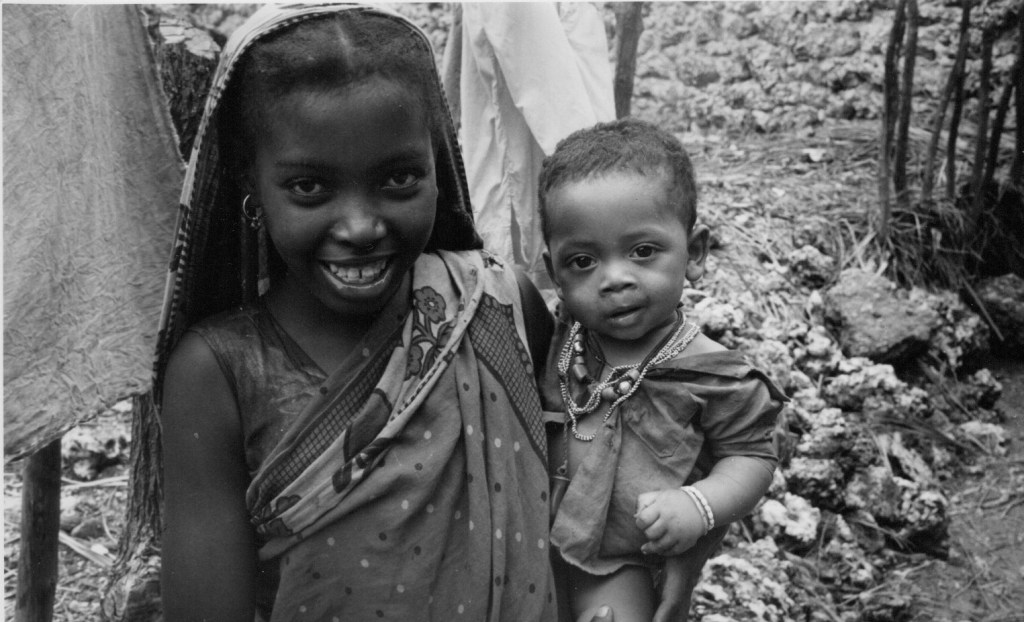

Opposite me an elderly matriarch, beautifully worked gold rings all down the sides of her ears, was coping with a small child, seasick, her granddaughter no doubt as they very much resembled each other. The small boat boy, agile and leggy rushed with a baling tin and poured water over the grandmother’s hands and the child’s dress to clean them up.

From under the forward cupboard part, cries of anguish came from those beneath, mostly women and a frantic call for a seasick can. As I got wetter and wetter, even the grandmother smiled at my drenched condition. The boat rolled and squirmed on, passing very narrowly two mashuas darting to our port side – a day for sailboat but not a small motorboat.

At last the Mkanda was reached – fetching out a khanga from my kikapu, I was able to wrap it around me take off my sudden shirt underneath it and everyone taking a good look at the operation but it was achieved with great decorum, though I fear I am so wet that I still leave a round damp patch where I sit. There’s still enough water in the channel to pass without sticking, we let down a passenger at a small landing place between the mangroves, he paddling off with a bushel of bananas on his head, and soon the open water is reached.

The sand dunes of Lamu appear and then the roofs of the houses, smouldering in the grey midday haze. Sea is a fine grey blue hue and calm, no trace of the wild waves of the open sea. My poor chicken has had a horrid journey, wedged between the luggage for safety: once or twice it had a flutter for freedom. The boat boy – can’t be more than nine or 10 – is a treasure, thin and lithe, he applies himself with energy to whatever task whether baling out the bilges, collecting the fares ( it is 7/- from Mtangawanda) or attending to boat and passengers needs. A gang of unattractive youth sit on the for’ard cover, refusing to move to lighten the load when we were in the rough patch.

Sailing in the Lamu channel

Faces of Pate